Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: 2012, America, art, Beauty, Blog, Blogging, Bob Dylan, Christianity, Concert review, Criticism, Deleuze, God, Grotesque, History, Hollywood, Hollywood Bowl, Instagram, iPhones, LA Times, Los Angeles, Media, mouth-breathing, Neverending Tour, News, Nietzsche, Queer Theory, reviews, Rock and Roll, Satan, Style, Writing, Young People

Ballad of an Untimely Man: Bob Dylan at the Hollywood Bowl

Taylor Black

Never Ending Tour. Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles, October 26, 2012.

Black, Taylor. “Ballad of an Untimely Man: Bob Dylan at the Hollywood Bowl.” American Quarterly 65:2 (2013), 397-404. © 2013 The American Studies Association. Reprinted with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

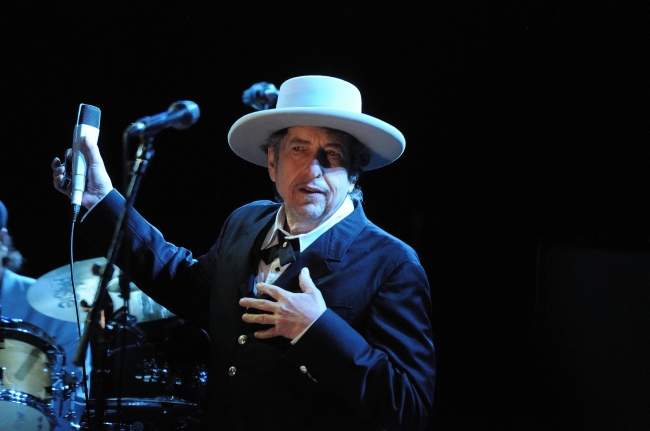

Figure 1.

“Bob Dylan, Live: By Paolo Brillo”

Unbeknownst to most of the very distracted and all-too-chatty members of the audience

for Bob Dylan’s Friday night show at the Hollywood Bowl on October 26, 2012, there was a moment when it became clear that the concert was something more like a war between Dylan and us. An untimely hero, Dylan has already predeceased himself; the man we heard that night was a man paving his victory trail into a world-to-come. As he spat and echoed his way through the always menacing “Ballad of a Thin Man,” he had won. Dylan rose up from his seat behind the baby grand piano, where he had spent most of the evening tapping his toe and crooning his hits, to grab a microphone, proceeding to prowl around the stage with a devilish grin and started in:

You walk into the room

With a pencil in your hand

You see somebody naked

You say, “Who is that man?”

You try so hard

But you don’t understand

Just what you’ll say when you get home

Because something is happening here,

But you don’t know what it is,

Do you, Mr. Jones?

A standout track from an already formidable collection of records making up Dylan’s 1965 album Highway 61 Revisited, “Ballad of a Thin Man” is a searing and grotesque send-up of the kinds of questions and ponderings that clutter the modern world and make it so noisy, as well as a thinly veiled mockery of a particularly rotund journalist that gained Mr. Dylan’s ire back on one of his infamous tours through England in the early sixties where he and his band electrified and busted up the genteel folk audiences who had at one time come to concerts to kneel beneath his gilded toes but who now called him Judas and screamed at him to go home. His fans wondered then why Bob Dylan had

forsaken them? Why couldn’t he respect the place given to him in the pantheon of American folk music and just sing the damn songs the folks wanted to hear? And how could this so-called voice of a generation commit sins of self-righteous individuality and still have the nerve to charge the public admission?

Still on the road and certainly still confusing and confounding audiences as he goes, Dylan has not escaped his own legacy enough to avoid the incessant drumbeat of passive-aggressive admiration and rabid nostalgia that his adoring public seems to love so much. In some ways, it may make sense that the man that we all know and refer to as America’s folksinger king may have made a quick escape from that sound and that scene just as soon as he was given credit and praise for making his way into it. Maybe the “folks” he has performed for and given himself to need Dylan even as they profess, as they always have and undoubtedly always will, that they don’t really like him anymore.

Maybe Dylan’s dedication to his “Never Ending Tour” is a prophetic one for him. Perhaps his path is led by a righteous dedication to singing to the reprobate consuming public, hurling his songs and his tricks at them like holy water on a possessed corpse. Perhaps Dylan just wants to show us how good and true a man can be.

Figure 2.

“Bob Dylan, Live: By Paolo Brillo”

For Dylan, the disappointment and confusion that his live performances create for his audience are charismatic effects that he is conscious of—a performative challenge he is able to make the most of. His concerts are opportunities for fans and listeners to gather before him and enter into the very banal but always deceptively thoughtful remarks about Dylan’s talents that followed him through his electrified barnstorm tour of England in 1966 and that mutated and still remained in the Hollywood Bowl’s echo chamber last October. While not relevant or, more pointedly, young enough to warrant orgasmic and angry accusations of being a Judas, Dylan was the occasion for many conversations that swirled around me during that night’s performance. In a different time and place, the responses I witnessed were just as mean and just as simple as

the infamous ones hurled at him on his electric tour of 1966.

With their faces aglow in the blue lights of iPhone text messages and Instagram updates, the weary patrons of the Hollywood Bowl amphitheater all carried the same burdens through Dylan’s October concert. Sticking to the contemporary party line given to us by insipid and sniveling rock journalists and parroted endlessly, the same questions were on everyone’s minds and mouths that night: “What song is this? I don’t even recognize it!” “His voice sure is shot!” “Oh my God: he is old!” Spoken from the mouths of babies, the

criticisms and thoughtful reflections on Dylan’s music and career have and will always be the same. Neither given to them by God nor placed in their beaks by the Devil, the catchphrases and resounding remarks on Dylan are unfortunate productions of modern listeners and audience members themselves. Bob Dylan’s appearance at the Hollywood Bowl was, for me and in the long run, an amazing and exhausting experience. Leaning back in my chair and letting his angry shouts and horror movie Wurlitzer sounds astound me, I looked, listened, and watched while Dylan worked himself over on this undeserving and unsuspecting crowd: the same one that had always been there.

Well, you walk into the room

Like a camel then you frown

You put your eyes in your pocket

And your nose on the ground

There ought to be a law

Against you comin’ around

You should be made

To wear earphones

Because something is happening here,

But you don’t know what it is,

Do you, Mr. Jones?

The song in question is, I must sheepishly admit, not so much a critique of Dylan’s audience as it is a painful prodding of the music critic’s motives and insinuations. The sin Mr. Jones commits that I am not guilty of, however, is critical relevance and a real commitment to American pop culture. In the original Highway 61 version of the song, Dylan moves through the strange and warped scenery like a cowpuncher, delivering jokes and sneers about the pitiable Mr. Jones’s walks through rooms he doesn’t know and characters he just can’t get. Unfolding behind the sound of a horror movie house organ, “Ballad of a Thin Man” sees a twisted and grotesque world through the critic’s eyes; with evangelistic zeal, Dylan writes the critic’s story on the wall as one burdened by

the sin of cheap confidence and covetous critical accuracy. At the end of the song, Dylan hands Mr. Jones his throat back and says, “Thanks for the loan.”

What in the world can this inflammatory song about the dead end of criticism do for someone who finds himself engaging in that very, precarious, industry? Considering that Dylan’s antagonistic relationship with his audience is undergirded by and historically based on his more heated and nasty relationship with the press (and with rock journalism in particular), it is important for me to consider my responsibilities and check my own hang-ups having to do with taste and style as I attempt to work my way through the tricky task of writing about Dylan. As Sean Wilentz so aptly put it in the introduction to his 2011 book Bob Dylan in America, critical reception of Dylan’s music is always

and already polarizing (1). Outside Dylan’s own insistence on this fact from the very first moments of his career, his commercial releases have received polarizing responses. That is, Wilentz argues, the very fact that Dylan has, we all know and he himself has admitted, released bad, or at least puzzling, albums (to name a few: Down in the Groove, Knocked Out Loaded, Live at Budokan, Self Portrait) has created two kinds of critical creatures: the Dylan fanatic and apologist who will accept anything from him and, as they say, would listen to him sing through the phone book, and the devil’s advocate who will, much

more carelessly and dangerously, always dispute the fact of Dylan’s genius and disregard anything he does. We take Dylan’s talent for granted as a culture when we consider his applications and performances of it; what we rarely do is humble ourselves before it or actually sit back and listen to what the man has to offer.

Devoted and dogmatic as I am with regard to Bob Dylan, I realize that it may be easy to lump me into the first of these categories. However, my interest in Dylan as a listener is and certainly ought to be different from my relationship to him as a writer and a thinker. At the heart of the critic’s reception of Dylan—either for or against—lies a cancerous and totalizing nostalgia that, Dylan himself would agree, is worse than death. Either through the apologists’ projections of themselves and their own histories with Dylan and his music or the naysayers’ annoying remarks about Dylan having lost his appeal (remarks

that, I hope I have made clear, have been there all along), the motor that drives critical responses to and affective receptions of Dylan’s work move through the world carrying nostalgia and sentimentality like a tumor.

The real challenge with situating Dylan is that to get it right the writer must take very careful steps through time and space—steps that understand the ways Dylan works against the grain of nostalgic time, marching his songs to the drumbeat of the future, toward an audience-to-come, an audience that might not, as Dylan well knows, ever get themselves together enough or get themselves to the great show at the end of the world. Moving back to his baby grand after “Ballad of a Thin Man” that night, Dylan and his band moved quickly into another strange number. Sounding like a futuristic take on Jimi Hendrix’s own version of the song, Dylan gave the audience a performance of

“All Along the Watchtower” that blended old and new, sounding like a song that had been around for thousands of years and that would still be sung a thousand years from now. Cinematic and visual as all Dylan’s songs are, “All Along the Watchtower” is a strange piece to consider among all his other works: clocking in at only eleven lines, Dylan still paints a horrifying picture of bleak land and scorched earth. Having once fought against the rigidity and spoiled sanctimony of American modernity, Dylan’s performance had a different effect that night at the Hollywood Bowl. Traveling away from and beneath the

homogenizing forces of our postmodern consumer culture and soaring into the aural space above his audience of mouth-breathing iPhone users and their constant comments over his songs, the lines in Dylan’s song took on new life as they imagined a new twilight of the idols.

“There’s must be some way out of here,” said the joker to the thief

“There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief ”

Businessmen, they drink my wine, plowmen dig my earth

None of them along the line know what any of it is worth

Of course, not everyone in attendance that evening deserves my scorn and disapproving glances back in time. Inside the amphitheater that night, I could see a small population of Dylan fans who, like myself, knew all the words and anticipated each of Dylan’s gestures and affectations to songs that others pretended not to recognize. Bootleg brothers of mine knew full well that Dylan wasn’t just making up new lyrics on the fly that evening as he crooned and soft-shoed his way through a version of “Tangled Up in Blue” he’d been doing since at least the early eighties. Not one of us turned to our neighbors at the beginning of the show and asked “Where is he?,” not knowing that Dylan performs from behind a keyboard or piano almost entirely these days and that

the tiny guy dressed in a black suit, green shirt, and gray Spanish cowboy hat behind the organ singing “Ooh wee” through a jaunty version of “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” was the man himself. Even worse, the LA Times itself, in a review of the show, perpetuated the audience’s general state of mind when it published complaints that the concert wasn’t aired on the Hollywood Bowl’s jumbotron that evening (2). No wonder the public was so consumed and distracted that evening: with no concert to see, what in the world were they to do? That night, thousands packed into the Hollywood Bowl, sat themselves in front of what even President Barack Obama has agreed is the most looming and

important figure to ever appear in American music and tuned themselves out (3). Thousands of hungry souls not knowing how to sit back and listen, plugged into pop culture and constantly interfacing with multiple forms of social media and digital communication squirming in their stadium seats, repeating every one of their doubts and perplexing questions at least twice to anyone who would listen to them that night. Almighty consumer citizens poured into the Hollywood Bowl that night only to leave estranged and wondering why they had made the effort in the first place.

Music critics and academic writers of pop cultural phenomena are, unfortunately, not much better than the audience at understanding and perpetuating musical and creative virtue when they see it. Like Mr. Jones, the cultural critic walks around with its eyes in its pocket and its nose on the ground—ever in search of relevance and meaning in any form of entertainment or popular media. Untimely as ever, it is not convenient that Dylan is still alive and performing himself and his music to audiences across the globe. No wonder our cranky and antagonistic bard is so set on his Never Ending Tour when most

forms of praise given unto him amount to passive-aggressive ways of telling him to drop dead. Having been called a legend almost from the word go, Dylan has been well aware of his precarious position in the mass production of himself as a musical icon and a spokesperson of a generation. “It’s like being in an Edgar Allan Poe story,” he told a 60 Minutes interviewer in 2004. “You’re just not that person everyone thinks you are. . . . [But then I realized] that the press and the media, they’re not the judge. God’s the judge. And the only person you have to think twice about lying to is yourself or God. The press

isn’t either one of them.” Like any untimely or heroic person, Dylan doesn’t believe he is God, only that he is closer to God than any of us. He has lived and experienced himself in this manner and with this in mind.

To write about Dylan is necessarily to answer the kinds of questions of time, history, and righteousness that all his songs insist on. You just can’t make it through “Ballad of a Thin Man,” for instance, without deciding which way you want to go when it is done: either you’re with Bob or you’re not; if you’re a writer or a critic, then the pressure is definitely placed on you as to what sorts of timely or untimely claims and phrases you want to fall from your mouth once the deal goes down. For the postmodern critic, relevance—be it political, pedagogical, or topical—is the trapdoor that is hard to miss when putting words to print with regard to this or that musical act of the moment. Like the iPhone-bound audience members witnessing but ultimately missing Dylan’s performance at the Hollywood Bowl that night, we are bound to lose out when we turn away from what’s happening right in front of us, when we put our ears to the ground and miss the songs being sung right to us. The tendency has been to dissociate the performer or the song from the present moment in which it is sung; to desire cross-wired mash-ups over pure productions of ingenuity and untimely grace; to stubbornly and clumsily seek out political narratives in order to announce an artist’s importance; to mistake hackneyed

nostalgia and overwrought citationality in pop music for futurity of some sort.

Like my bootleg brothers spread throughout the crowd at Dylan’s Hollywood Bowl show, relevance is not on my side. This untimeliness is, however, unlike nostalgia in that it points toward what forces and creative elements can’t be seen by contemporary logic rather than overindulging in scripts and narratives that we all know too well. Songs, if they succeed in any way in and of themselves, are concepts—rolls of the dice on a future moment and of a future landscape. When Dylan penned his “Ballad of a Thin Man,” he was surely venting, painting a picture of one or, more likely, a whole host of characters

who really did impinge on and limit his existence as an artist with confounding amounts and forms of media attention on him. Still, though, his castigations and grotesque lamentations remain as possible sites of future ideas and lines of flight toward righteous creative forms in the world to come. To hear and anticipate these thunderous echoes, all you have to do is listen. Against the maelstrom of noisy complaints and a glowing sea of cell phone screens, I held on tight that evening at the Hollywood Bowl as Dylan growled and his voice echoed through the amphitheater and out into the wilderness. Shadowy and imposing, Dylan’s words and his graven image conjured up, if just for those two hours he was onstage, a world lost and a world gone wrong.

Notes

1. Sean Wilentz, Bob Dylan in America (New York: Double Day, 2010), 4–5.

2. Randall Roberts, “Review: Bob Dylan at the Hollywood Bowl,” Los Angeles Times, October 27, 2012.

3. Natalie Jennings, “Presidential Medal of Freedom: Obama Honors Bob Dylan, Madeleine Albright, and Others,” Washington Post, May 29, 2012

Filed under: Amy Ray, deleuze, Dirt, Divine, Dust, exploration, exploration as joke, freedom, Funeral Songs, gay rights, God, hangover, Haunting, Jesus Christ, Jimmie Rogers, Laramie, lesbian music, Meat, Meridian, nihilsm, nothing, nowhere, Spooks, suicide, Terroir, testosterone, violence, Wyoming

She’s Got To Be

Taylor Black

July 2011

When I was very young I wanted to be a witch. No, not in the sun and moon-worshipping, pentacle-wearing way, but a real witch, the kind you see in movies. In fact, my obsession was specifically with the Wicked Witch from The Wizard of Oz, and until I was around seven or eight years old I not only idolized her mentally and emotionally but also dressed as her more often than not. Cloaked in black, witch’s hat in place and riding around my family’s house on a broomstick, I felt most at home in my own skin.

As the years passed and all the confusing feelings and sensations brought on by puberty began to wax, all the imperiousness and dark glamour that influenced my idea of myself as a young witch transformed into what might be generously called a bourgeoning gender and sexual identity. As I ceased riding around on broom sticks and began to ponder my life as a matured adult being I then began to slowly cultivate a different idea of myself as a person found myself drawn to women that were, like Miss Witch: cold, commanding and horribly imposing.

I then spent the rest of my teenage years basking in the glow of these women and this wicked, feminized vision of myself. Luckily, I then found myself able to manipulate my icy form of majestic detachment as a sort of self-defense mechanism as I hurtled through all the drama one might expect for a depraved young faggot growing up in the oppressively masculine, drab Bible Belt South. More tragically, I suppose, I also felt a certain distance —from other people, from lovers, from myself, from my own body.

Living in the ivory tower of my fantasies, I began to feel all alone. And then soon I was. Everything would be okay, would stay in its rightful place, so long as I didn’t look into a mirror. Sex felt alright if I didn’t have to be touched or feel anything good. Friendships were okay if I did all the talking but none of the sharing. Being a member of my family was fine just as long as no one mentioned or thought about my future as a human being, much less as a gendered one.

Fast-forward to my sad, stony face staring around New York City, my new home. Running just as fast as I could out of North Carolina and pointing my toes, or my broomstick, due north, I landed on its shores at age 18, expecting something of a community and some kind of solid sense of identity to come my way. The queer world I found myself in was not one I was able to fold myself so easily into. Drunk on (post-)identity politics and the prescriptive narratives and vocabularies that went along with it, I felt even more failed than before. Knee-deep in sinners presumably like myself and settled into a community of queers and a city full of failures, I still felt my obvious lack of identification and hope for my sorry state of sexual abjection and gender dysphoria to be a burden and a source of that same loneliness I’d become so accustomed to.

Which brings me, however belatedly, to the song that I intended to focus squarely on this week, but that got waylaid by this little confessional. Not just the title for this mistaken autobiography of mine, but also the title of the second song off of Amy Ray’s most recent solo record Didn’t It Feel Kinder, \”She\’s Got To Be\” is the closest to an anthem or to a trans/queer audiobiography that I might be able to relate to.

Odd as it is, I find a lot of myself in this road-weary, road-worn song Amy Ray has written about her butchness and her own relationship to gender dysphoria. Across generations, bodies and sexualities, I find this very personal, yet complicated and even cagey, “anthem” of hers comforting. For better or worse, the song stands out on the album it appears on, but also in the whole of Amy Ray’s catalogue. Following behind the

the bass and the beat comes Amy Ray singing in a boyish falsetto. Her voice is deceptively sweet, sounding almost like some sort of fucked up version of David Cassidy or Donny Osmond. If you don’t listen carefully to the lyrics in the first verse it would be easy to think of the song as a love song for another woman.

She’s got to be with me always

To make sense of the skin I’m in

Sometimes it gets dangerous

And lonely to defend

Marking time with every change

It’s hard to love this woman in me

The first time I listened to the song was at a concert, standing just a few feet from Amy Ray and her band as she closed her eyes and started in on this devastatingly personal and personalizing ballad to her self. Mind you, I’d heard the song a whole lot of times in the weeks leading up to the show on record, but I hadn’t listened to what it was saying. More than that, though, I don’t think it would have willfully occurred to me that a song sung about queerness might have anything to say to me, isolated as I have become in my mixed-up, useless image of myself.

Amy Ray’s song romances the sadness I’ve always had but never clearly felt or understood. “She’s Got To Be” is everything I need it to be: an anthem about losing gracefully. It is resigned, undone, incomplete and, at least to me, absolutely gorgeous. As I’ve said, you can’t sing a song in praise of some-thing about yourself that you didn’t create or do. If you try and sing triumphantly about a game you can’t win, you’ll lose out in the end. You lost before you began. But, what you can do is sing in the name of your failure—not to over-essentialize or lionize it, but to wrap yourself in it and feel at home. You can stop fighting against yourself if you stop pretending you might be able to win.

She’s the one that stills the seas

Finds the truth in this anarchy

Dives the depth of every age

Keeps this body and knows the shape

The chorus sounds anthemic, but is really more of a spell that Amy Ray casts in her singing of it. Instead of celebrating, it’s creating. It’s resolving. You’ve got to be to be free.

I will love I will protect this love

It was hard to get

I will love and I will protect this love

And it’s anarchy

Standing at the show, drunk on gin and staggered by the weight of what I was suddenly hearing, I began to cry quietly—something, as you might imagine, that doesn’t come naturally or easily to me. The revelation in the song is in Amy Ray’s willingness to give in to herself, to stop fighting and start becoming. Central to my own melancholy regarding any queer or trans narrative I might be able to apply to myself is a recognition that my fantasies and desires—of my self, my body and my sexual expression—can’t translate into anything. This song, like me, is resigned to its failure and in love with its chaos.

The thing that made me cry is the impossibility—of gender, cohesion, language, existence—Amy Ray realizes and demonstrates in her performance of the song. I cried not because I was sad for her, though, but because I knew what she was expressing, felt what she was admitting to have failed at. From my early years on a broomstick to my isolated attempts at finding a home for myself and a useful meaning for my desires, I stood rejoicing in this sweet little song of hers about giving up and staying put. In order to love yourself and become you’ve got to learn to leave well enough alone. Instead of breaking you down, failure can be full of capacity, a way of being and becoming in and of itself.

As I have come to believe in my twilight: when there’s nowhere to go it can feel a lot less lonely and horrifying to stay put, to remain right where you seem to belong. “She’s Got To Be” isn’t a queer anthem, but it’s an anthem to queer-ness; to self-love, instead of misguided self-praise. In place of the noise of rebellion and the silent echoes of loneliness came this song of self-love and affirmation to save me. In every subsequent listen, I remain to be wooed by its sweet sounds of failure, caught up in the romantic melody of resignation.

Filed under: Benediction, Camille Paglia, Cube steak, Divine, dumb dumbs, dumdums, Elena Glasberg, God, Jesus Christ, John Waters, Lady Gaga, Meat, MTV, nothing, nowhere, Pink Flamingos, queer theory, Uncategorized

A Benediction

Sunday, 09/19/10

We know what you were thinking: so much for Junebug vs Hurricane! Those two dolts haven’t gotten enough executive between the two of them to finish an email, much less keep a blog up and running for very long!

Well, dear reader, you’re very wrong – and I must say, you shouldn’t say or think such nasty things about us! Have some faith! We were simply taking the summer off to recoup and deal with other things: our good friend Hurricane met a lady-friend and spent that time being punch drunk, and I my sweet summer months wandering the streets of London and New York just plain drunk.

You can rest assured that you’ll have access to our wonderful thoughts and musical asides in the cold weeks to come, but for the moment we have felt it necessary to emerge from the sticky warmth of our hibernation to set the record straight once and for all on every last conversation having to do with dear Miss Gaga.

In general, we try and keep our noses out of so-called pop cultural trends and discussions that are beneath both our tastes as well as our radars, but, as you might imagine, the Lady Gaga phenomenon is not one we have been successful at hiding from. Consider this intervention more like a benediction: this is the last thought that you or either of us will need to think about Gaga, and this is the last conversation having to do with the cultural trend that she represents. Anything you enjoy or appreciate in the blog entry to come you may credit both me and my partner in crime with duly; however, if you find yourself offended you should feel free to direct your blame and anger at me, Junebug, since I know my much wiser and more tactful friend would surely have worded this in a much different way.

So, without further prefacing or adieu, we present to you:

The Official Junebug vs Hurricane Dismissal of Little Miss Gaga:

1. Her music is horrible, and you know it.

2. We do not accept her as a so-called “queer” artist and do not find it interesting or even remarkable that scores of homosexuals find her interesting. For one thing, queers from either side of the aisle have never been—and apparently will never be—known for their taste in music. Let us not forget Quentin Crisp’s decades old, but still pertinent and wise words on this matter: “A lifetime of disco music is a high price to pay for one’s sexuality.”

3. Neither her “music” nor her “performances,” whether on stage or off, “do” anything. No, Miss Paglia, she is not stealing or appropriating anything from Madonna or anyone else—plagiarism is, we fully admit, part of the creative process and not something to get up in arms about (mostly because it can lead to very tiresome and tautological kinds of discussions, on both ends). However, criticism and scholarship from the queer academy and from better bred members of the pop culture press that attempt to credit Miss Gaga’s music, performances and public appearances for “doing” anything both oversimplify and miss the point of musical production to be worthwhile in and of themselves without having to intervene in any political movements, change gender, do gender, represent sexuality or uplift queerness. Music is music and it is only valuable for being music. Music is capable of producing music.

4. We think it’s very annoying that Miss Gaga has decided to become the new gay diva. Admittedly, she is smart for recognizing a space for herself in the queer market place. It has been a while since homosexual men in America, the UK and worse have had someone to look up to or to weep over since Whitney is too busy being a crackhead, Beynocé has proven herself to be a fair-weather friend, the pale and weepy homos that once followed Tori Amos have been restless lately and it doesn’t look like poor Judy Garland will be lifting her pie-faced self out of the grave anytime soon.

However, we snub our noses at everything she has done and wonder why other otherwise intelligent queers have fallen for it hook line and sinker—we know they can’t love her for her songs!

4a. We are annoyed with Lady Gaga-the-political-leader in the following ways: from her maudlin attempts at shoring up the hearts and minds of the gays with all of her “You are my little monsters!” business to her very misguided and nosey intervention in “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” proceedings in Congress to the stupid new title of her stupid new record “Born This Way.”

5. Who cares if she wore a meat dress to the VMAs? We all remember Pink Flamingos and know full well that Divine already stuck a big slab of cube steak in her panties way back when. This is not a who-done-it-first kind of claim, mind you, but a Divine-shoved-meat-in-her-cunt-years-ago-for-our-sins kind of claim. I mean, we’re supposed to be schocked by Miss Gaga when we have the memory of Divine written into our very souls? Please?

As a matter of fact, to (roughly) quote John Waters on the Gaga thing: “I’ve seen it before. The only thing nice I’d have to say about her is that she’s got a pretty ugly face.”

6. Lady Gaga is a trap. She only represents a new trend—in fashion, pop culture criticism, journalism and homosexuality. Fashion trends are arbitrary sets of rules that change arbitrarily from year-to-year without doing or saying anything interesting, unique or queer in the least. In times of doubt, let us not look to or participate in fashion trends for our sense of our selves, our community or our politics. The visibility Lady Gaga offers queers in the marketplace and in the middle of American pop culture is a trap, and we suspect that those of us who have not relished our time in the darkness wisely might have fallen for the insulting invitation into the ugly and banal spotlight that her presence has offered us.

7. Did we say her music sucks? It does gey stuck in your head, true, but that just reminds us of the feeling we get waiting in the lobby at the Dentist’s office or getting carsick in the back of a cab while someone else (someone with no taste or sympathy) is controlling the radio dial.

So, to sum up our little rant: Lady Gaga is annoying and so are arguments for or against what she does or doesn’t do to culture and politics. These kinds of conversations abound, but are all based in knee-jerk reaction and very generous and misguided uses of political theory and cultural studies.

If anyone involved in these kinds of discussions needs a cautionary tale they only need look back upon the very embarrassing “debates” around poor little Madonna from the eighties and early nineties—we all thought those conversations to be terribly pertinent and relevant at the time, but look at her now! The bitch’s off speaking with a Scottish accent doing God knows what.

I shudder to think at how silly all this will seem once the dust settles, the wind blows in a different direction and we have all accepted the utter hollow and annoying essence of our dear Little Lady Gaga.

May 26, 2010

My partner Juney Bug’s been regaling our readers with the song of the loathsome, fearsome hag. The hag — and don’t get this wrong, ya’ll — is no one to pity. She is not a Christian figure, exactly. No pity and no mercy for the white gal at the end of the bar, please! She don’t need it. She – unlike the rest of us – is Right With God. She, with her tricks and manners, her suitors, a gin and a tonic to lean over, and the end of the night coming on too strong. Like all the Lonely Girls and Barroom Girls, she doesn’t want the night to end. Help our hag keep those colored lights flashing; come closer, and sit down beside her. Tell her a story – if you can get a word in edgewise. And if you’ve got that sad-eyed air about you, fella, hardly a nickel in your pocket, maybe those shoulders carried the weight better in younger days, well then, you just might be the hag’s long lost brother: the beautiful loser. What the hag is to country and down home twang, the beautiful loser is to rock n roll and the Jersey shore. While the hag never left town and her bitterness is deeply grounded, like her moneymaker, into that barstool, the loser couldn’t sit still. You could say he was born to run, to ride his cliché 90 miles an hour down a dead end street. Consequently he is always on the road, lost, and always coming home.

Johnny was a schoolboy when he heard his first Beatles song,

‘Love me do,’ I think it was. From there it didn’t take him long.

Got himself a guitar, used to play every night,

Now he’s in a rock ‘n’ roll outfit,

And everything’s all right, don’t you know?

“Love Me Do I think it was” – It’s a quote, of course, and thus the most genuine syllables of a song of love and theft. A long hall of mirrors and the corridors of forgettings and violent crossings out of memory wind the lyric. The stagey way that memory is produced – I think it was — and its middle class, polite locution gives away where these shooting star poseurs come from – mama’s house, or in the case of Bad Company, England. This is the kind of bad company one finds in the discomfort of the suburbs (or 1970s Flatbush), the place where nothing is supposed to ever happen and the blues come borrowed all the way from the Delta through The Stones and Led Zep on to American top 40 ubiquity.

Love me do I think it was. And maybe it was. Maybe it was for me, too. I used to listen all afternoon, piling the stereo arm high with vinyl LPs, the Beatles and Dylan, The Stones, and Judy Collins, Odetta. Where was my little brother? All I remember of David is my excoriating disgust that when offered as a present any album in the world, the fool chose Tom Jones, Live. He actually wanted to listen to an under-talented ass who swiveled his hips at the screaming female fans who threw their panties on stage. It makes sense then that David would go on to love Bad Company. Like Tom Jones they wore tight pants and glittery outfits to accentuate their heterosexuality. Liking them was the mark of a true boy, a suburban, melancholic boy. A white boy, like my brother David.

Johnny told his mama, hey, ‘Mama, I’m goin’ away.

I’m gonna hit the big time, gonna be a big star someday’, Yeah.

Mama came to the door with a teardrop in her eye.

Johnny said, ‘Don’t cry, mama, smile and wave good-bye’.

It’s no accident that mama comes up in the second verse. She is the fount of the loser’s self-love, the lover he wants to escape and to perform for. Little Rockstars are mama’s boys. In their badness — especially in their rebellions — they prove themselves tied ever more to mama. Everyone wants to save the loser. In this bath of unwanted maternal attention the loser perfects defenselessness as the ultimate defense. His signature concession — You may be right – predicts another bender: Hey mama I’m going away.

Remember the hag? The lady sitting at the end of the bar? Well, she’s gotta move over. There’s another sibling rivaling for the bartender’s attention. The lesbian with the dead brother is a new cliché (and oxymoron). We coulda been him. Maybe wanted to be him. Weren’t allowed to be him. Or refused to be him. But in not getting what we wanted or felt we deserved, we survive all the guys we could not be. Poor, unlucky, survivors.

Johnny made a record, Went straight up to number one,

Suddenly everyone loved to hear him sing the song.

Watching the world go by, surprising it goes so fast.

Johnny looked around him and said, ‘Well, I made the big time at last’.

Among my brother’s things is a notebook with cockroach brown pasteboard covers, the kind that you find in old-fashioned office supply stores. In it the tab forShooting Star is meticulously inscribed. My brother took up playing the guitar in prison the way Malcolm X taught himself to read. In prison you do for yourself what you’d let others do for you in the outside world. The results of the loss of freedom can be impressive. By the time his sentence was complete, David played a pretty good guitar.

One afternoon soon after his release, my brother performed an acoustic version of the strangely affable power rocker. He was crashing at our mother’s apartment in Marine Park, one of NYC’s last havens of white ethnics. He was home; I was visiting from grad school in the midwest. I had been circling jobs for him in the local paper. He shot down every demeaning suggestion, but gracefully, without rancor. “This is a good entry level position,” I offered. “You’re probably right” he’d evade. How can a rock star be a bagel boy? Yet as I was playing the sane older sibling I was fighting my surprise at his studious guitar playing. I admit it: I was jealous. You see, I had always been the rock star in the family. I was the one whose band played CBGBs. But I put down the guitar. Who was I to tell him to get real about working some dumb job? Wasn’t I in grad school studying literature, trying just as hard as he was to escape the fate of the ordinary? We both nursed our rock star dreams. Our narcissisms collided, overlapped.

As it turns out, there has always been a job opening for a Shooting Star:

Johnny died one night, died in his bed,

Bottle of whiskey, sleeping tablets by his head.

Johnny’s life passed him by like a warm summer day,

If you listen to the wind you can still hear him play

Don’t you know that you are a shooting star,

Don’t you know, yeah, don’t you know…..

Every beautiful loser sings “Shooting Star” at his own funeral, years before he actually dies, in the mournful cadence of manly self-possession. He’s long down the road from the boy who once cried out “look ma –.” He knows now that no one can look away; no one can ever save him. And it is his utterly calm refusal to be saved that draws us to the beautiful loser. I mean, would you actually want Him to have come down off that cross, knowing his investment in his own sacrifice? Until that afternoon I don’t think I ever realized how fully jealous I must have been all of my life of my beloved little brother, the beautiful loser.

I think David might have learned more about what he wanted in prison than I managed to in grad school. I know he never became a recidivist. Yet I in my way have never gotten out of my institutionalization. No, I seem to even be fighting my way in deeper. And he’s long gone.

But if you listen to the wind you can still hear him play …..

My thoughts so often come back to Dylan, who also wrote a Shooting Star of his own:

All good people are praying/ it’s the last temptation, the last account

Last time you might hear the sermon on the mount

Last radio is playing

Seen a shooting star tonight slip away

Tomorrow will be another day

Guess it’s too late to say the things to you that you needed to hear me say

Seen a shooting star tonight slip away

Maybe Bad Company’s “Shooting Star” is the last song … playing? If so, I often hear its opening guitar chords so balanced, detached, equanimous: All our deaths are sure to come. Don’t You Know?

Don’t you know, yeah yeah, Don’t you know that you are a shooting star,

Don’t you know, don’t you know. Don’t you know that you are

a shooting star, And all the world will love you just as long,

As long as you are.

Filed under: Uncategorized

And, at long last:

Entering Lucinda’s World Without Tears

(Listen to) Real Live Bleeding Fingers and Broken Guitar Strings

Photographic dialogues

Beneath your skin

Pornographic episodes

Screaming sin

In my very slow, languid process of thinking and feeling my way through this record—and indeed in my outline for this very paper—my intention was to go through it song by song and in direct chronological order—until last night. Driving around the empty, rain-soaked streets of Chinatown at three in the morning following an unproductive stint in New York University’s Bobst Library, I indulged this rare moment of desolate isolation that I’d normally have to embark on a long road trip out of the busy and cluttered atmosphere of the Northeast by putting World Without Tears on and turning up the sound. With my car’s poor little CD-player accidentally set to random, the album began in an unusually loud and ragged way; instead of the sweet sad vibrato of her song “Fruits of My Labor” that normally eases you into Lucinda’s magnificent, horrible old world, I found myself being shouted at by the ragged, screeching sound of the guitar that makes up the introduction to her very staggering anthem “Real Live Bleeding Fingers and Broken Guitar Strings.”

Shattered nerves

Itchy Skin

Dirty words

And heroin blurs

Not one to be outdone by her band, however, the shocks and the reverberations that ensue past the musical interlude are all Lucinda. Like the ordinary introduction to the album, this song is all about vibrato—a kind of dance or clash between the lead guitar that drips and shakes its notes out of itself and Lucinda’s voice that quivers and howls its way out of her worn old throat. Unlike “Fruits of My Labor,” however “Real Live Bleeding Fingers” frightens and calls its listeners to attention rather than easing them into with something that sounds deceptively beautiful and tender.

You’ve got a sense of humor

You’re a mystery

I heard a rumor

You’re making history

To get back to my story, though: as I drove the streets of New York, wary of my aloneness yet comforted by it too, I almost turned the song to something a little softer; considering the remoteness of the atmosphere and the weariness of my disposition, I figured I really ought to play one of her long ballads and let it swallow both me and the humid, empty night up with its drippy lap steel interludes and plodding turns of phrases. However, as to not upset fate or disrespect my dear Lucinda, I dutifully remained inside the space of “Real Live Bleeding Fingers,” a song—as I’ve heard her say—both about seeing lover after lover and relationship and relationship fall victim to “heroin blurs,” but also, oddly enough, about the solo work of Paul Westerberg. As the song began to finish its march over my nerves as well as the sonic space of an unsuspecting Canal Street, the last verse shouted at me and told me exactly what I should say and think about my love not only of the music but also of the misery, of the disaster.

The Coda listed at the beginning of this piece constitutes the emotional and spiritual arch of my affection for Lucinda’s music. But, to understand my true appreciation for her music it is necessary to think through my identification—nay, my devotion—for her. You see, to really listen to music you have to not only engage with and open yourself up to the performer/composer, but you have to have faith in them. This faith certainly takes time and is not something you can donate to every song you put you and your senses through, but this kind of pure listening experience is not only about enjoyment and pop pleasure, but also a kind of labor. In order to love Lucinda, you have to cultivate your belief in her. As she has proclaimed on high, this process of belief and adoration means you’ve gotta climb all the way inside her tragedy, and then get yourself right behind her majesty.

Glory, Glory //We’ve Killed the Beast!

(Listen to) Atonement

Come on, Come on, Come on

Kill the rats in the gutter

I do realize that it’s very gay for me to refer to the object of my affection and musical appreciation a queen, and you should know, if you haven’t already or always assumed, that I do in fact suffer from a debilitating case of homosexuality—however, I’d like to work through and around this very staid, over-determined notion of the tragic gay man and his love for his tragic diva queens, if only so that I may return to the term without all of its heavy metaphorical baggage.

Shake the clammy hand

Repeat the 23rd psalm

Make you understand

Where it was you went wrong

After all, there are, I will deign to argue, different types of these bruised, yet majestic icons of queer femininity and different sets of gay male subjects that inhabit their mighty kingdoms. The most obvious and significant example of the gay icon is, of course, Judy Garland—not so much because of her performance in The Wizard of Oz, which actually constituted the more populist American image of her—but the tragedies and the public performances of addiction and some sort of psychosis that attract her many homo queens under her withering wings.

Blinded by glittery diamonds

Resting on crooked fingers

Shaded eyes they are the ones

Who’ll lead you to your deliverance

Believe it or not, I do not belong to the club of tragedy queens who bask in the undertow of Miss Garland and do not find much pleasure in witnessing the breakdowns, pill and gin ravages and on-stage failures that mark her late—and arguably, as a result, her entire—career. Unfortunately for these queens, they get failure all wrong. Like Wayne Koestenbaum’s very astute depiction of another kind of queen—the opera queen’s troublesome, failed tastes and the public reception of their pathological, utter pleasurelessness, all summed up in their questionable appreciation of the opera.

However these cultural metaphors also work to insult me, which is, of course of even greater importance and concern. You see, terms—like failure, queen, tragedy—are sources of creative and indeed affective inspiration and fidelity for both me and my academic work, but because they so commonly understood as jokes on and about gay men and their tastes, I can’t seem to employ them explicitly with a straight face. You see, originary and constitutive as they are, as queer metaphors, they have been subtracted of any amount of emotional capacity or even discursive flexibility. They are so gay, so sad and, in the end, so thoroughly understood and explained by the world that they work to constantly explain and insult us until we, like poor Miss Garland, find ourselves face down in our party dresses in piles of (what we hope is) our own filth.

Dry your tears. The Tragedy Queen’s pitiful reign is over, but only if we really want it. The joke’s only on us if we let it. The camp, glib relationship Garland’s tragedy queens approach her with is, on the one hand, tricky because it is sympathetic. In other words, they love to witness Judy’s tumbles and stumbles from afar, and the highest form of emotional labor that’s required beyond this sort of ironic spectatorship is sympathy: who would want that? Even more terrible is the sad fact that these sad old homos don’t even know that to real people, it is precisely this taste for tragic tragedy that tells them everything they need to know about the emotional state of all homosexual men in the world: sad.

Let me give you something good to eat

Bite down hard ‘til it sticks between your teeth

I do hope you I haven’t confused you, dear reader. I realize that just before this castigation of tragedy queens I spent pages and pages flirting with disaster and ruin and hinting that I might lay out a roadmap for turning failure and tragedy into forms of amusement and pleasure. So, you may be asking yourself, what’s the difference between Judy Garland’s tragedy queens and me, a homosexual who has already—and repeatedly—confessed his unquestioned and potentially problematic identification with and love for Lucinda? After all, I am drawn to her, in large part, because of a strong desire on my part to bear witness to the many losses as well as partake and indulge myself in the great sadness with which she hones and performs her songs. It is necessary to empathize with Lucinda in order to appreciate her, to, as I have explained, cultivate your faith in her and all of the beautiful tragedies that come along.

It’s time to come on (…come on, come on…) under Lucinda’s wing. As you see in the lyrics I have chopped up and laid down for you throughout this section and also—if you follow orders correctly—hear, “Atonement” is a song that is composed of and composes religious decrees. More than just a topical, satirical take on evangelical forms of invocation and manipulation, this is, like “Real Live Bleeding Fingers,” another one of those songs that will break you down and turn you out, if you’re willing. Indeed, as it marches on and on and over its audience, this very bossy, aggressive, jarring song constitutes Lucinda’s great march to victory. More than that, though, it’s also a kind of blessing, or, rather, an invitation to any of us who would like to follow here into her kingdom. Indeed, just like Lucinda, the song is hard to take, too much—but, if you resist the urge to turn the song down or tune her out, you might get the wonderful experience of having her swallow you up. Remain in this lovely, debilitating sonic state, under the dizzying influence of the unrepentant sound of Lucinda’s frightening hoots and hollers that keep moving and moving and you will have received your blessing, and will then find yourself falling, like withering flowers at her feet.

(Listen to) Fruits Of My Labor: the Beginning and the End

Baby, see how I been livin’

You know, even though, like any good homosexual, I loved The Wizard of Oz growing up, I always hated poor old, pie-faced Dorothy. To this day, I cannot forgive her totally unrealistic and style-less decision to forgo a chance to reign over the whole, plush kingdom of Oz at the end of the film and return to her drab, colorless existence back home in Kansas (even typing those words feels to banal for my own good). But what really sealed the deal for me as a young man was that she threw a bucket of water on The Wicked Witch of the West: the only truly wonderful and powerful character in that film, and indeed the object of my affection and impersonation as a young thing (until my practice of dressing in a hate and cape and flying around may family’s home on a broomstick was wisely—yet too belatedly—called off around age eight). My adolescent love for this character, who had immediately caused fear and confusion in me has influenced my tastes as well as provided the ontological structure of my affective fidelity today. I like sadness, failure and tragedy only out of a love for wickedness—in other words, I like that these terms which unsettle and unnerve nearly everyone else on the planet might be a way of living fabulously, egregiously and fiercely.

Lavendar, lotus blossoms too

Water the dirt, flowers last for you

Baby

sweet

baby

My desire to become, like the Witch, someone who frightened others and lived in an isolated, yet vast universe that was all hers is one way in which I overcame my own alienation as a very homosexual, strangely gendered kid in a fiercely monotone, Southern Baptist culture. With the Witch as my guide, I then saw a way of moving around the debilitating effects of this isolation and loneliness that would have otherwise caused in me various personality disorders, realizing there was a more magical way to be the outcast—that if considered and maintained correctly, inborn deficiencies and insistent social and personal handicaps could actually be the source of power.

Tangerines and persimmons

And sugarcane

Grapes and honeydew melons

Enough fit for a queen

Lemon trees don’t make a sound

‘Til branches bend and fruit falls to the ground

So what’s there to say about my lifelong penchant for the absurd, the wicked and the truly tragic that can animate the rest of this little devotional to Lucinda? And, what’s really so much more astonishing and unique about her and her whole suitcase of sadness and failure that she carries along with her? Well, it’s that she cultivates and mitigates her own tragedies and weaves them into her persona in ways that are more awe-some than that Dorothy could ever be or those actually tragic, detached tragedy queens might ever imagine. Indeed, that very religious and powerful word awe-some has become so commonplace and misused that, like tragedy and failure, has lost its capacity to really mean or do anything at all; it has become a dead word.

I been tryin’ to enjoy all the fruits of my labor

I been cryin’ for you boy but truth is my savior

But, how can we imbibe these terms with even more power than they may have ever had? How can you stimulate and recodify terms and descriptors that are supposed to handicap and explain you away? Thankfully, the kind of sorcery that is required to respond to this dilemma is my—and Lucinda’s—specialty. As I have explained, Lucinda’s power over her personal failures is maintained through the hold she is able to have over her audience, whose total faith and devotion is absolutely a requirement. Before this is possible, however, she needed a system of recasting tragedy into song, image and style—and thankfully, Lucinda—witch that she is—has been able to do just this. Through her flirtatiously, evil version of this process, she has made a career of recasting and rephrasing her haggardness and sorrow into something that makes music and creates devoted followers.

Baby, sweet baby if it’s all the same

Take the glory any day over the fame

Baby, sweet baby

For her, failure is not simply about failing, but also about creativity and possibility. Likewise, tragedy is not something to lament, but to wallow around in—a process of becoming-fabulous as well as a form of presentation that allows you to take hold over other people. She is truly awe-some in all the ways we have forgotten God ever was: beautiful, alarming, imposing, magnificent, horrible, overwhelming, beautiful and wonderful. Through her, the word is alive once again.

Filed under: Funeral Songs, Haunting, Lucinda Williams, nothing, nowhere, Pineola, Red Dirt, Southern Gothic, Spooks, Terroir, Uncategorized

World Without Tears: A Devotional, Part 1

Taylor Black

May 2010

Coda:

I climbed all the way inside

Your tragedy

I got behind

The majesty

Of the different shapes

In every note

The endless tapes

Of every word you wrote

Preface: Misery Loves Company

Just as that tired, worn out old saying says: misery loves company. While the remark is normally intended as a kind of passive-aggressive jab directed at the kind of person who tortures their friends, family and really any poor charitable soul who will listen with a never-ending sympathy of complaints and woe-is-me’s, for me, it’s a way of life. As you plunge your self and your own sympathies into this piece, you will see that my own love of misery’s company is really the motor behind all my thoughts and affections, weepy and strange as they may be.

And another thing, dear reader: whether or not you’ve figured it out by now, the string of ideas, gushes and aphorisms that might otherwise be politely referred to as a “paper” will be largely—and, I hope, wonderfully—self-indulgent. There will be more affection in my writing than analysis, and I will concern myself more with how things feel and sound as I say them than defend them as ground-breaking ideas or concepts—I will be writing about music after all. At the very least, I hope you read things you want to hear and that the sight of me wallowing in my own wickedness is entertaining.

We are entering dangerous territory, or, rather, I should say I am entering into a project that’s about my absolute favorite album done by my absolute favorite artist. Why is this dangerous? Well, as most of my previous “academic” work has been conventionally analytical, I haven’t spent much time or intellectual energy lingering on the things in my life that I love. I will shamefully admit that for a long while, my interpretation of doing scholarly work has been about making arguments about things or situating myself into theoretical discussions that have been raging on in one form or another for-probably-ever. In this state of blissful recalcitrance, I found it easiest to make my arguments and my very defensive(?) claims about things I felt a certain detachment from; the idea of responding to and writing about something I love so religiously as music and a figure I identify with so wholly might lead me into embarrassing, confessional territory.

So, with all of that said, I would simply like to emphasize the fact that with this new turn in my work (let’s call it my musical turn for the time being), I am pushing my thoughts and my academic productions away from its defensive, readerly roots towards somewhere and something more celebratory. The joke I brought up in the first sentence will not be, at the end of all of this, on me; as I ruminate on Lucinda Williams’ World Without Tears I will hold it up as an ode to loneliness and despair, all the while doing my own part to draw out and wallow around in the loooove in “Misery Loves Company.”

In terms of a method, mine will be not be very methodological. For starters, you will detect a stark lack of citation in what lays ahead of you—this is not because (believe it or not) I don’t care what other people have to say about Lucinda or any of the musical genres her music and my depictions of her engage with, but because I want to resist the rather litigious urge in academic scholarship to prove what’s said critically and creatively by citing, engaging and situating compulsorily. My thoughts and indeed the sonic space inside my head where they reside and are generated have not come from a vacuum. In similar ways that songwriters can say that this or that piece is inspired by this or that artist or genre, there is a kind of interplay between this paper and the texts—in this case, Wayne Koestenbaum’s The Queens Throat, José Muñoz’ Cruising Utopia, Jimmy McDonough’s new Tammy Wynette: Tragic Country Queen and Hélène Cixous’ Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing— I have been inhabiting during the writing process. While I engage with these pieces to the extent that their thoughts and modes of writing ring in my mind and my ear while I myself do work, I will not attempt to condense or be totally responsible for them, as I try and work with this model of residual, ghostly intertextuality through my own thoughts and feelings.

Secondly, I will confess that the idea of explicitly explaining, describing or deconstructing Lucinda’s music and the album I am approaching gives me even more angst than attempting to be responsible for the contents of a book. Music, like literature and academic scholarship alike, is a process of creativity and failure, and its products and productions should not be approached in order to determine what is they represent or explain, but instead honored for what they do, as well as for what sensations, feelings, misgivings and thoughts they create in the hearing of them. So, just as these authors and these books will be singing their songs in my head while I write, so too while the contents of World Without Tears play while I move from word to word and page to page. As I move ahead, I will rarely approach a song in any literal way or attempt to take it apart—either lyrically or otherwise. Instead, I will let my thoughts and feelings flow against the backdrop of particular tracks on the album, which I will dutifully and possibly excruciatingly play on repeat while I construct the different spaces of my piece. When I have done so, I will list the song and request that my reader try and listen while they read so that they too can sense the rhythm and the affective space with which this piece comes to be. When I do sense a particularly cogent or uncanny relevance of Lucinda’s lyrics for these songs, I will chop them up and place them—in italics—throughout the piece.

With all of that out of the way, I promise not to defend myself or my feelings anymore throughout this work, which is really more like a religious devotional than any kind of academic prose I can imagine. I’m sure I will contradict myself here and there, and my love of Lucinda and tragedy may confound or even fatigue my reader, but I do hope you will at least appereciate my earnestness and the purity of whatever feelings I express here. But why? And shouldn’t I be ashamed at such a disgusting display? Isn’t all of this self-loathing instead of self-loving? Or am I just being ironic? One very easy way to get out these pointed, if obvious, slew of accusations and doubts about my so-called love for misery and the truly miserable would be to revert to some kind of psychoanalytic explanation about being from the Bible Belt South and having internalized and maybe even romanticized all of the most terrible components of the melodramatic Fire and Brimstone culture I was brought up in; or worse, I could simply lean on my identity as a homosexual man and sight some well-known, meaningless tropes about queerness and tragedy as a way of placating you and letting me and my work off the hook as “camp.”

Her Wonderful Wickedness

(Listen to) Righteously

-

-

-

-

- Think this through

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- I laid it down for you every time

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Respect me I give you what’s mine

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- You’re entirely way too fine

-

-

-

In all kinds of rather obvious ways, my decision to undertake this Lucinda record is a mistake. First of all, it’s not her most beloved body of work; 1998’s Car Wheels on a Gravel Road is the one album critics and journalists love to love. With its cinematic, narrative songs that weave their ways in and out of moldy, humid corners of the Delta region of the American South, Car Wheels combines just the right amount of folksy realness with meticulously high-brow literaryness to please the kinds of critics who felt invested in roots music but isolated from the explosion of decidedly middling, middlebrow pop music coming out of Nashville. Here you had something as conceptual and sophomorically intellectual as a Bob Dylan or Neil Young album falling from the heavy, weary lips of a woman who had not only conceived of, but actually lived the very southern stories she sung about, all delivered in her thick, muggy southern drawl. Even more exciting for journalists and critics alike was the gossip surrounding and the drama that weighted down the production of the album; taking over four years, three different incantations, three different producers and countless victims employed along the way, once Car Wheels finally came out, Lucinda had managed to gain a reputation for herself as a bitchy, histrionic perfectionist—and (the mostly male) world of rock criticism and journalism still, to this day, can’t seem to publish anything without using that “perfectionist” word, just like no one had ever said it or thought it before they regurgitated it. Leave it to them.

-

- Arms around my waist

-

- You get a taste of how good this can be

-

- Be the man you ought to tenderly

-

- You’re entirely way too fine

You see, or as you already assume or expect, our Ms. Williams is a bit hard to take. For one, she is a perfectionist, and, leaving all gendered epithets aside, doesn’t hide her emotions very well. While most of her fans and critics are both men, their relationship is totally different, and what they see and hear in Lucinda varies completely. For the detached rock critic, weighed down by their strange mix of irony and corporate professionalism, Lucinda’s story is sort of a joke on her, something to talk about ad nauseam.

When you run your hand

All up and run it back down my leg

Get excited and bite my neck

Get me all worked up like that

You don’t have to prove

-

-

-

- Your manhood to me constantly

-

-

-

-

-

- I know you’re the man can’t you see

-

-

-

-

-

- I love you Righteously

-

-

I

The song “Righteously” that is blaring in my ears while I write this is an anthem to power and glory through abjection. In some ways related to Tammy Wynette’s epic song of total, devastating and, in the end, failed devotion to her man, Lucinda’s song is, in some ways, a promise of hers to the man she’s got in her life. However, it’s also a wicked line of flight away from the sentiments expressed in “Stand By Your Man”; beyond and behind her coy promises of righteous love is the real power of this song, which actually, magically stimulates, entices and interpellates her man’s devotion. For the middle aged white men I see at her shows, however, there is a spark in their eyes and a look of abject devotion on their face that lets me know they get it: they don’t look down on Lucinda, they look up at her, and while the sad and sorrowful definitely falls out of her whenever she opens her mouth to sing, it is her fierce, flirtatious and wicked delivery and composure that transforms her tragedies into an elixir that draws her devotees in and brings them down to their grateful knees.

Arms around my waist

You get a taste of how good this can be

Be the man you ought to tenderly

Stand up for me

Approaching Lucinda, Our Beautiful Loser

(Listen to) Sweet Side

-

-

- So you don’t always show your sweet side…

-

Just this side of strange in comparison with the other men at Lucinda’s concerts, I will admit that the main reason I enjoy myself at her shows, though, is mitigated through my sense as well as my perception of her anxiety that is normally—almost ritually—played out each evening she performs in a certain chronology. When she finally makes her way on stage (always very belatedly, in my notable experience), she brings with her an unsettling sort of presence. Lucinda’s affect and disposition is weighed down by a stony, stoic, silent stage fright for the first third of the set, as she moves her way through a handful of amazingly slow, overwrought, plodding, pitiful old songs (the kinds anyone else would tell you to not perform in concert, much less for the first part of the damn set!) allthewhile averting the gaze of the audience and dissociating her from the stage she is performing on.

-

-

-

- You run yourself ragged tryin’ to be strong

-

-

You feel bad when you done nothin’ wrong

Love got all confused with anger and pride

So much abuse on such a little child

Someone you trusted told you to shut up

Now there’s a pain in your gut that you can’t get rid of

After this, thanks to nerves and/or whatever liquor she’s got in her cup up there on stage (she says she drinks Grand Marnier to coat her throat, so there’s at least that…), our once sheepish heroine warms up a bit, maintaining her anxieties and displeasures about her surroundings. Peppering—or, if you’re not into such tenuous forms of spectatorship, cluttering—her performance with false starts and vulgar outbursts, Lucinda has come out of her shell a bit (the last example that comes to mind is her, very seriously and angrily, stopping mid-song to say “Who do I have to fuck to get a fucking fan up here? It’s fucking hot!” Other times I’ve heard her scold people for talking during her set, asking them if they’d like to “fucking do it” themselves)—finally opening herself up to the crowd, only to turn, venomously and breathtakingly, against them.

You were screamed at and kicked over and over

Now you always feel sick and you can’t keep a lover

-

-

-

- You get defensive at every turn

-

-

-

-

-

- You’re overly sensitive and overly concerned

-

-

Few precious memories no lullabies

Hollowed out centuries of lies

A Lucinda Williams concert then, and finally, comes to an end in a flurry of hard-rocking, loud songs that are as frayed at the edges, but orgasmically so. By the time you’re ready to leave, Lucinda has certainly done what a good showman is supposed to do, which is give you your money’s worth by keeping you on the edge of your seat and the tips of your toes. The angst and constant fear of total disaster that guides both Lucinda and her audience through the evening come full circle by the final bows, as she drags out the blaring, cathartic portion of the evening until everyone is drunk and damn well spent. Bill Buford, in his—confused, rather patronizing—depiction of Lucinda published in The New Yorker not long after the release of Car Wheels summed up one of her shows in this way:

- “. . .it’s still possible to see a live show in which she gets a little carried away-and she always seems to be on the verge of getting a little carried away-and hear almost the entire oeuvre, as was the case about eighteen months ago at New York’s Irving Plaza, when Williams’s [sic] encores went on longer than the act, and the audience emerged, after nearly two and a half hours, thoroughly spent, not only by the duration of the program but also by the unforgiving rawness of the songs.”1

What I cannot grasp here—and indeed what I intend to turn on its head, is this very expected, boring depiction of Lucinda as merely a crazy bitch who happens to have written some amazing songs—that being a fan of hers or even being in the presence of her is a thoroughly harrowing thing for someone to be put through—is the lack of empathy that Mr. Buford carries in his self-confessed appreciation of Lucinda’s music. And, of course, he’s not the only person or journalist to put Lucinda and her concert performances in such a glib light (incidentally, a Time Out New York blurb that hinted at possible trainwrecks and meltdowns at one of her concerts was the cause of a night of drama and bitching from Lucinda, who did not get over or stop mentioning it for the entire evening); perhaps this condescending sketch of Lucinda-the-crazy-person is their backhanded, backwards way of complimenting the strength of her music, which they appreciate and understand through very staid tropes of the beautiful loser: the outsider/tortured artist whose brilliance shines in spite and at the expense of themselves (think: Townes Van Zandt, Janis Joplin, Billie Holliday, Tammy Wynette, and on and on). You see, for these folks, Lucinda and her music alike are only fascinating because she’s a train wreck; all descriptions of her, in turn, quickly become cautionary tales.

-

-

-

- You’re tough as steel and you keep your chin up

-

-

-

-

-

- You don’t ever feel like you’re good enough

-

-

Well, as I’ve said and will say again and again, this tale about our Miss Williams will not be a cautionary, ironic or detached one. In order to love her music, you’ve got to appreciate the angst, romance in the disaster and wallow along with her as she moves through her songs and makes them work. True listening is an act faith on the part of the listener—and when the image of the singer/songwriter is just as present in the song as the notes and the lyrics that guide them through, a determined empathy and, dare I say, a religious affection are both completely necessary.

-

- I’ll stick by you baby through thick and thin

-

-

- No matter what kind of shape you’re in

-

Cause I’ve seen your sweet side…

Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: Dixie Chicks, Femme, Goldschlager, Kernersville, Lesbians, Melissa Etheridge, Mountain Dew, Taylor Black, The Odyssey, Winston-Salem

Taylor Black

04/08/10

[Listeners’ Guide: These here blue links are songs that should be played behind your reading of the story. The words don’t work otherwise, this shit is choreographed! Click where it says click and you’ll have a nice time. xo, Jbg]

Saturday nights are Missy Barker’s favorite. Even though she had already had herself three other Saturday nights in the past week, the stars seemed aligned tonight. It was Saturday night after all.

“Memaw! Can I have $20? I’ll get it back to you once my man Blake pays me back next week.”

Her grandmother sighed, tried to look away from her reflection in the TV screen, awoke a bit, collected herself and then lit a cigarette—Tareytons 100s if you are the kind of person who likes banal information like that—and, after taking a long, gratuitous drag put down her lighter on the coffee stand, flipped on the lamp next to her Lazyboy and answered her dear Missy’s request:

“What the hell are you going to do with $20? Don’t you think for a minute you can just buy a bunch of beer and invite half of the ingrates of Kernersville over here tonight—it’s not gonna happen, like hell you will.”

“Memaw!”—a name Missy, her brothers and now even her own parents used in place of the one her parents gave her, the one she was recognized by when hope still seemed salvageable, before people started calling her ma’am and waiting for her to shuffle off to the forevereverafter. In fact, Dora [I know what you’re thinking: “Dora? You mean like Dora the Explorer?” No, Doe-ra, as in Dooooooe-rrrrra], her name before Memaw, suited her. After all, a name like “Memaw” that is affectionate; it’s meant for someone who washes clothes all day long, cooks pots and pots of pinto beans and wakes every morning just to tell you how much you mean to her. But Dora, Dora Dora: the woman’s about as folksy as as a truckstop and as feminine as one of the eighteen wheelers huddled together in the parking lot outside, waiting for their drivers to put down the 17-year old call boys they’re ravishing and the “Surf and Turf” dinner specials they’re eating.”—“shut the hell up and tell me where your money is. You know I’m good for it. Besides, I wouldn’t be asking you if I hadn’t gotten my money stolen at The Odyssey the other night.”

Poor, petulant Missy.

With the mind of a child and common sense of an inbred Rottweiler, she really believes that she’s important enough to get robbed.

In fact, no one stole money from her; hell, everyone in there is basically fluid bonded, since it was the only homosexual establishment within a 30 mile radius. Everyone knows your name at The Odyssey, but only out of habit. The same folks are always doing and saying the same things there every night, wasting what’s left of their paychecks on drinks composed mostly of knockoff mixers and sprinkled with watered down liquors. Like dogs who circle and circle their vomit before finally giving in and eating in, the denizens of Winston-Salem’s hottest, and only, gay club made their eternal rounds each and every night inside its black-lit halls.

“Go on and get a twenty from my room. I got a pile of money on top of my chest of drawers, but don’t think for a second I don’t know how much is there, don’t even do it Melissa Jean. You take your $20 and get your lily white ass on out of this house so I can get some peace and quiet: your brother was nice enough to show me how to tape all my stories that I miss during the day [napping, going to the pawn shop to shoot the shit with her friend Peggy who’s been working there since her husband’s disability checks started going to his growing collection of Sudafed and jet fuel that he was keeping out back in his toolshed, and stopping in at the liquor store to buy 6 airplane bottles of Smirnoff at a time—anything more would be unladylike…).”

Missy opened the door to Dora’s cell and thought to herself that the smell of mildew was finally beginning to overpower the smell of 40 years of cigarette smoke that had before that time overpowered the entire abode. Memaw’s sentence on earth was certainly coming to a close sooner rather than later. There was something in the air that made it certain.

As she slide a $20 into the coin-pocket of her new [knockoff, bought from Rose’s, tossed aside not from last season’s collection, but from 1998’s collection…brought down to North Carolina just for her to shove herself into] True Religion’s she paused. . .and then told herself that dangerous phrase that she said so much that it almost became a tic, the one that made her feel butch but really just admitted how little she had to lose:

“Fuck it.”

Missy then checked herself out in the mirror, liked what she saw—save the unsightly bumps on her chest that even her sports-bra and extra-large men’s dress shirt from couldn’t do away with—grabbed an unsolicited $10 bill and her old Memaw’s discarded wedding ring and she was ready to go.