Filed under: Uncategorized | Tags: 2012, America, art, Beauty, Blog, Blogging, Bob Dylan, Christianity, Concert review, Criticism, Deleuze, God, Grotesque, History, Hollywood, Hollywood Bowl, Instagram, iPhones, LA Times, Los Angeles, Media, mouth-breathing, Neverending Tour, News, Nietzsche, Queer Theory, reviews, Rock and Roll, Satan, Style, Writing, Young People

Ballad of an Untimely Man: Bob Dylan at the Hollywood Bowl

Taylor Black

Never Ending Tour. Hollywood Bowl, Los Angeles, October 26, 2012.

Black, Taylor. “Ballad of an Untimely Man: Bob Dylan at the Hollywood Bowl.” American Quarterly 65:2 (2013), 397-404. © 2013 The American Studies Association. Reprinted with permission of Johns Hopkins University Press.

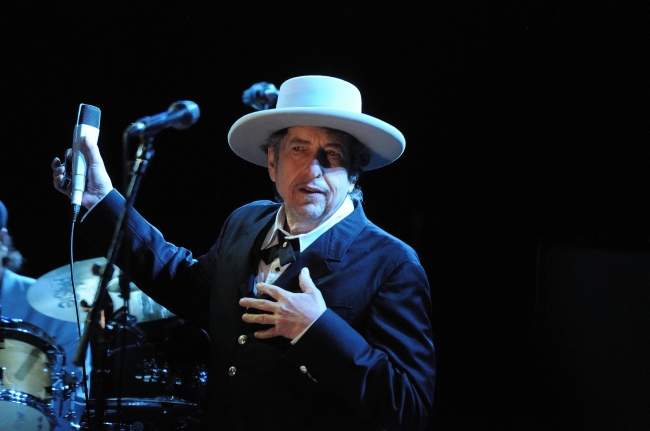

Figure 1.

“Bob Dylan, Live: By Paolo Brillo”

Unbeknownst to most of the very distracted and all-too-chatty members of the audience

for Bob Dylan’s Friday night show at the Hollywood Bowl on October 26, 2012, there was a moment when it became clear that the concert was something more like a war between Dylan and us. An untimely hero, Dylan has already predeceased himself; the man we heard that night was a man paving his victory trail into a world-to-come. As he spat and echoed his way through the always menacing “Ballad of a Thin Man,” he had won. Dylan rose up from his seat behind the baby grand piano, where he had spent most of the evening tapping his toe and crooning his hits, to grab a microphone, proceeding to prowl around the stage with a devilish grin and started in:

You walk into the room

With a pencil in your hand

You see somebody naked

You say, “Who is that man?”

You try so hard

But you don’t understand

Just what you’ll say when you get home

Because something is happening here,

But you don’t know what it is,

Do you, Mr. Jones?

A standout track from an already formidable collection of records making up Dylan’s 1965 album Highway 61 Revisited, “Ballad of a Thin Man” is a searing and grotesque send-up of the kinds of questions and ponderings that clutter the modern world and make it so noisy, as well as a thinly veiled mockery of a particularly rotund journalist that gained Mr. Dylan’s ire back on one of his infamous tours through England in the early sixties where he and his band electrified and busted up the genteel folk audiences who had at one time come to concerts to kneel beneath his gilded toes but who now called him Judas and screamed at him to go home. His fans wondered then why Bob Dylan had

forsaken them? Why couldn’t he respect the place given to him in the pantheon of American folk music and just sing the damn songs the folks wanted to hear? And how could this so-called voice of a generation commit sins of self-righteous individuality and still have the nerve to charge the public admission?

Still on the road and certainly still confusing and confounding audiences as he goes, Dylan has not escaped his own legacy enough to avoid the incessant drumbeat of passive-aggressive admiration and rabid nostalgia that his adoring public seems to love so much. In some ways, it may make sense that the man that we all know and refer to as America’s folksinger king may have made a quick escape from that sound and that scene just as soon as he was given credit and praise for making his way into it. Maybe the “folks” he has performed for and given himself to need Dylan even as they profess, as they always have and undoubtedly always will, that they don’t really like him anymore.

Maybe Dylan’s dedication to his “Never Ending Tour” is a prophetic one for him. Perhaps his path is led by a righteous dedication to singing to the reprobate consuming public, hurling his songs and his tricks at them like holy water on a possessed corpse. Perhaps Dylan just wants to show us how good and true a man can be.

Figure 2.

“Bob Dylan, Live: By Paolo Brillo”

For Dylan, the disappointment and confusion that his live performances create for his audience are charismatic effects that he is conscious of—a performative challenge he is able to make the most of. His concerts are opportunities for fans and listeners to gather before him and enter into the very banal but always deceptively thoughtful remarks about Dylan’s talents that followed him through his electrified barnstorm tour of England in 1966 and that mutated and still remained in the Hollywood Bowl’s echo chamber last October. While not relevant or, more pointedly, young enough to warrant orgasmic and angry accusations of being a Judas, Dylan was the occasion for many conversations that swirled around me during that night’s performance. In a different time and place, the responses I witnessed were just as mean and just as simple as

the infamous ones hurled at him on his electric tour of 1966.

With their faces aglow in the blue lights of iPhone text messages and Instagram updates, the weary patrons of the Hollywood Bowl amphitheater all carried the same burdens through Dylan’s October concert. Sticking to the contemporary party line given to us by insipid and sniveling rock journalists and parroted endlessly, the same questions were on everyone’s minds and mouths that night: “What song is this? I don’t even recognize it!” “His voice sure is shot!” “Oh my God: he is old!” Spoken from the mouths of babies, the

criticisms and thoughtful reflections on Dylan’s music and career have and will always be the same. Neither given to them by God nor placed in their beaks by the Devil, the catchphrases and resounding remarks on Dylan are unfortunate productions of modern listeners and audience members themselves. Bob Dylan’s appearance at the Hollywood Bowl was, for me and in the long run, an amazing and exhausting experience. Leaning back in my chair and letting his angry shouts and horror movie Wurlitzer sounds astound me, I looked, listened, and watched while Dylan worked himself over on this undeserving and unsuspecting crowd: the same one that had always been there.

Well, you walk into the room

Like a camel then you frown

You put your eyes in your pocket

And your nose on the ground

There ought to be a law

Against you comin’ around

You should be made

To wear earphones

Because something is happening here,

But you don’t know what it is,

Do you, Mr. Jones?

The song in question is, I must sheepishly admit, not so much a critique of Dylan’s audience as it is a painful prodding of the music critic’s motives and insinuations. The sin Mr. Jones commits that I am not guilty of, however, is critical relevance and a real commitment to American pop culture. In the original Highway 61 version of the song, Dylan moves through the strange and warped scenery like a cowpuncher, delivering jokes and sneers about the pitiable Mr. Jones’s walks through rooms he doesn’t know and characters he just can’t get. Unfolding behind the sound of a horror movie house organ, “Ballad of a Thin Man” sees a twisted and grotesque world through the critic’s eyes; with evangelistic zeal, Dylan writes the critic’s story on the wall as one burdened by

the sin of cheap confidence and covetous critical accuracy. At the end of the song, Dylan hands Mr. Jones his throat back and says, “Thanks for the loan.”

What in the world can this inflammatory song about the dead end of criticism do for someone who finds himself engaging in that very, precarious, industry? Considering that Dylan’s antagonistic relationship with his audience is undergirded by and historically based on his more heated and nasty relationship with the press (and with rock journalism in particular), it is important for me to consider my responsibilities and check my own hang-ups having to do with taste and style as I attempt to work my way through the tricky task of writing about Dylan. As Sean Wilentz so aptly put it in the introduction to his 2011 book Bob Dylan in America, critical reception of Dylan’s music is always

and already polarizing (1). Outside Dylan’s own insistence on this fact from the very first moments of his career, his commercial releases have received polarizing responses. That is, Wilentz argues, the very fact that Dylan has, we all know and he himself has admitted, released bad, or at least puzzling, albums (to name a few: Down in the Groove, Knocked Out Loaded, Live at Budokan, Self Portrait) has created two kinds of critical creatures: the Dylan fanatic and apologist who will accept anything from him and, as they say, would listen to him sing through the phone book, and the devil’s advocate who will, much

more carelessly and dangerously, always dispute the fact of Dylan’s genius and disregard anything he does. We take Dylan’s talent for granted as a culture when we consider his applications and performances of it; what we rarely do is humble ourselves before it or actually sit back and listen to what the man has to offer.

Devoted and dogmatic as I am with regard to Bob Dylan, I realize that it may be easy to lump me into the first of these categories. However, my interest in Dylan as a listener is and certainly ought to be different from my relationship to him as a writer and a thinker. At the heart of the critic’s reception of Dylan—either for or against—lies a cancerous and totalizing nostalgia that, Dylan himself would agree, is worse than death. Either through the apologists’ projections of themselves and their own histories with Dylan and his music or the naysayers’ annoying remarks about Dylan having lost his appeal (remarks

that, I hope I have made clear, have been there all along), the motor that drives critical responses to and affective receptions of Dylan’s work move through the world carrying nostalgia and sentimentality like a tumor.

The real challenge with situating Dylan is that to get it right the writer must take very careful steps through time and space—steps that understand the ways Dylan works against the grain of nostalgic time, marching his songs to the drumbeat of the future, toward an audience-to-come, an audience that might not, as Dylan well knows, ever get themselves together enough or get themselves to the great show at the end of the world. Moving back to his baby grand after “Ballad of a Thin Man” that night, Dylan and his band moved quickly into another strange number. Sounding like a futuristic take on Jimi Hendrix’s own version of the song, Dylan gave the audience a performance of

“All Along the Watchtower” that blended old and new, sounding like a song that had been around for thousands of years and that would still be sung a thousand years from now. Cinematic and visual as all Dylan’s songs are, “All Along the Watchtower” is a strange piece to consider among all his other works: clocking in at only eleven lines, Dylan still paints a horrifying picture of bleak land and scorched earth. Having once fought against the rigidity and spoiled sanctimony of American modernity, Dylan’s performance had a different effect that night at the Hollywood Bowl. Traveling away from and beneath the

homogenizing forces of our postmodern consumer culture and soaring into the aural space above his audience of mouth-breathing iPhone users and their constant comments over his songs, the lines in Dylan’s song took on new life as they imagined a new twilight of the idols.

“There’s must be some way out of here,” said the joker to the thief

“There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief ”

Businessmen, they drink my wine, plowmen dig my earth

None of them along the line know what any of it is worth

Of course, not everyone in attendance that evening deserves my scorn and disapproving glances back in time. Inside the amphitheater that night, I could see a small population of Dylan fans who, like myself, knew all the words and anticipated each of Dylan’s gestures and affectations to songs that others pretended not to recognize. Bootleg brothers of mine knew full well that Dylan wasn’t just making up new lyrics on the fly that evening as he crooned and soft-shoed his way through a version of “Tangled Up in Blue” he’d been doing since at least the early eighties. Not one of us turned to our neighbors at the beginning of the show and asked “Where is he?,” not knowing that Dylan performs from behind a keyboard or piano almost entirely these days and that

the tiny guy dressed in a black suit, green shirt, and gray Spanish cowboy hat behind the organ singing “Ooh wee” through a jaunty version of “You Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere” was the man himself. Even worse, the LA Times itself, in a review of the show, perpetuated the audience’s general state of mind when it published complaints that the concert wasn’t aired on the Hollywood Bowl’s jumbotron that evening (2). No wonder the public was so consumed and distracted that evening: with no concert to see, what in the world were they to do? That night, thousands packed into the Hollywood Bowl, sat themselves in front of what even President Barack Obama has agreed is the most looming and

important figure to ever appear in American music and tuned themselves out (3). Thousands of hungry souls not knowing how to sit back and listen, plugged into pop culture and constantly interfacing with multiple forms of social media and digital communication squirming in their stadium seats, repeating every one of their doubts and perplexing questions at least twice to anyone who would listen to them that night. Almighty consumer citizens poured into the Hollywood Bowl that night only to leave estranged and wondering why they had made the effort in the first place.

Music critics and academic writers of pop cultural phenomena are, unfortunately, not much better than the audience at understanding and perpetuating musical and creative virtue when they see it. Like Mr. Jones, the cultural critic walks around with its eyes in its pocket and its nose on the ground—ever in search of relevance and meaning in any form of entertainment or popular media. Untimely as ever, it is not convenient that Dylan is still alive and performing himself and his music to audiences across the globe. No wonder our cranky and antagonistic bard is so set on his Never Ending Tour when most

forms of praise given unto him amount to passive-aggressive ways of telling him to drop dead. Having been called a legend almost from the word go, Dylan has been well aware of his precarious position in the mass production of himself as a musical icon and a spokesperson of a generation. “It’s like being in an Edgar Allan Poe story,” he told a 60 Minutes interviewer in 2004. “You’re just not that person everyone thinks you are. . . . [But then I realized] that the press and the media, they’re not the judge. God’s the judge. And the only person you have to think twice about lying to is yourself or God. The press

isn’t either one of them.” Like any untimely or heroic person, Dylan doesn’t believe he is God, only that he is closer to God than any of us. He has lived and experienced himself in this manner and with this in mind.

To write about Dylan is necessarily to answer the kinds of questions of time, history, and righteousness that all his songs insist on. You just can’t make it through “Ballad of a Thin Man,” for instance, without deciding which way you want to go when it is done: either you’re with Bob or you’re not; if you’re a writer or a critic, then the pressure is definitely placed on you as to what sorts of timely or untimely claims and phrases you want to fall from your mouth once the deal goes down. For the postmodern critic, relevance—be it political, pedagogical, or topical—is the trapdoor that is hard to miss when putting words to print with regard to this or that musical act of the moment. Like the iPhone-bound audience members witnessing but ultimately missing Dylan’s performance at the Hollywood Bowl that night, we are bound to lose out when we turn away from what’s happening right in front of us, when we put our ears to the ground and miss the songs being sung right to us. The tendency has been to dissociate the performer or the song from the present moment in which it is sung; to desire cross-wired mash-ups over pure productions of ingenuity and untimely grace; to stubbornly and clumsily seek out political narratives in order to announce an artist’s importance; to mistake hackneyed

nostalgia and overwrought citationality in pop music for futurity of some sort.

Like my bootleg brothers spread throughout the crowd at Dylan’s Hollywood Bowl show, relevance is not on my side. This untimeliness is, however, unlike nostalgia in that it points toward what forces and creative elements can’t be seen by contemporary logic rather than overindulging in scripts and narratives that we all know too well. Songs, if they succeed in any way in and of themselves, are concepts—rolls of the dice on a future moment and of a future landscape. When Dylan penned his “Ballad of a Thin Man,” he was surely venting, painting a picture of one or, more likely, a whole host of characters

who really did impinge on and limit his existence as an artist with confounding amounts and forms of media attention on him. Still, though, his castigations and grotesque lamentations remain as possible sites of future ideas and lines of flight toward righteous creative forms in the world to come. To hear and anticipate these thunderous echoes, all you have to do is listen. Against the maelstrom of noisy complaints and a glowing sea of cell phone screens, I held on tight that evening at the Hollywood Bowl as Dylan growled and his voice echoed through the amphitheater and out into the wilderness. Shadowy and imposing, Dylan’s words and his graven image conjured up, if just for those two hours he was onstage, a world lost and a world gone wrong.

Notes

1. Sean Wilentz, Bob Dylan in America (New York: Double Day, 2010), 4–5.

2. Randall Roberts, “Review: Bob Dylan at the Hollywood Bowl,” Los Angeles Times, October 27, 2012.

3. Natalie Jennings, “Presidential Medal of Freedom: Obama Honors Bob Dylan, Madeleine Albright, and Others,” Washington Post, May 29, 2012