Filed under: Benediction, Camille Paglia, Cube steak, Divine, dumb dumbs, dumdums, Elena Glasberg, God, Jesus Christ, John Waters, Lady Gaga, Meat, MTV, nothing, nowhere, Pink Flamingos, queer theory, Uncategorized

A Benediction

Sunday, 09/19/10

We know what you were thinking: so much for Junebug vs Hurricane! Those two dolts haven’t gotten enough executive between the two of them to finish an email, much less keep a blog up and running for very long!

Well, dear reader, you’re very wrong – and I must say, you shouldn’t say or think such nasty things about us! Have some faith! We were simply taking the summer off to recoup and deal with other things: our good friend Hurricane met a lady-friend and spent that time being punch drunk, and I my sweet summer months wandering the streets of London and New York just plain drunk.

You can rest assured that you’ll have access to our wonderful thoughts and musical asides in the cold weeks to come, but for the moment we have felt it necessary to emerge from the sticky warmth of our hibernation to set the record straight once and for all on every last conversation having to do with dear Miss Gaga.

In general, we try and keep our noses out of so-called pop cultural trends and discussions that are beneath both our tastes as well as our radars, but, as you might imagine, the Lady Gaga phenomenon is not one we have been successful at hiding from. Consider this intervention more like a benediction: this is the last thought that you or either of us will need to think about Gaga, and this is the last conversation having to do with the cultural trend that she represents. Anything you enjoy or appreciate in the blog entry to come you may credit both me and my partner in crime with duly; however, if you find yourself offended you should feel free to direct your blame and anger at me, Junebug, since I know my much wiser and more tactful friend would surely have worded this in a much different way.

So, without further prefacing or adieu, we present to you:

The Official Junebug vs Hurricane Dismissal of Little Miss Gaga:

1. Her music is horrible, and you know it.

2. We do not accept her as a so-called “queer” artist and do not find it interesting or even remarkable that scores of homosexuals find her interesting. For one thing, queers from either side of the aisle have never been—and apparently will never be—known for their taste in music. Let us not forget Quentin Crisp’s decades old, but still pertinent and wise words on this matter: “A lifetime of disco music is a high price to pay for one’s sexuality.”

3. Neither her “music” nor her “performances,” whether on stage or off, “do” anything. No, Miss Paglia, she is not stealing or appropriating anything from Madonna or anyone else—plagiarism is, we fully admit, part of the creative process and not something to get up in arms about (mostly because it can lead to very tiresome and tautological kinds of discussions, on both ends). However, criticism and scholarship from the queer academy and from better bred members of the pop culture press that attempt to credit Miss Gaga’s music, performances and public appearances for “doing” anything both oversimplify and miss the point of musical production to be worthwhile in and of themselves without having to intervene in any political movements, change gender, do gender, represent sexuality or uplift queerness. Music is music and it is only valuable for being music. Music is capable of producing music.

4. We think it’s very annoying that Miss Gaga has decided to become the new gay diva. Admittedly, she is smart for recognizing a space for herself in the queer market place. It has been a while since homosexual men in America, the UK and worse have had someone to look up to or to weep over since Whitney is too busy being a crackhead, Beynocé has proven herself to be a fair-weather friend, the pale and weepy homos that once followed Tori Amos have been restless lately and it doesn’t look like poor Judy Garland will be lifting her pie-faced self out of the grave anytime soon.

However, we snub our noses at everything she has done and wonder why other otherwise intelligent queers have fallen for it hook line and sinker—we know they can’t love her for her songs!

4a. We are annoyed with Lady Gaga-the-political-leader in the following ways: from her maudlin attempts at shoring up the hearts and minds of the gays with all of her “You are my little monsters!” business to her very misguided and nosey intervention in “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” proceedings in Congress to the stupid new title of her stupid new record “Born This Way.”

5. Who cares if she wore a meat dress to the VMAs? We all remember Pink Flamingos and know full well that Divine already stuck a big slab of cube steak in her panties way back when. This is not a who-done-it-first kind of claim, mind you, but a Divine-shoved-meat-in-her-cunt-years-ago-for-our-sins kind of claim. I mean, we’re supposed to be schocked by Miss Gaga when we have the memory of Divine written into our very souls? Please?

As a matter of fact, to (roughly) quote John Waters on the Gaga thing: “I’ve seen it before. The only thing nice I’d have to say about her is that she’s got a pretty ugly face.”

6. Lady Gaga is a trap. She only represents a new trend—in fashion, pop culture criticism, journalism and homosexuality. Fashion trends are arbitrary sets of rules that change arbitrarily from year-to-year without doing or saying anything interesting, unique or queer in the least. In times of doubt, let us not look to or participate in fashion trends for our sense of our selves, our community or our politics. The visibility Lady Gaga offers queers in the marketplace and in the middle of American pop culture is a trap, and we suspect that those of us who have not relished our time in the darkness wisely might have fallen for the insulting invitation into the ugly and banal spotlight that her presence has offered us.

7. Did we say her music sucks? It does gey stuck in your head, true, but that just reminds us of the feeling we get waiting in the lobby at the Dentist’s office or getting carsick in the back of a cab while someone else (someone with no taste or sympathy) is controlling the radio dial.

So, to sum up our little rant: Lady Gaga is annoying and so are arguments for or against what she does or doesn’t do to culture and politics. These kinds of conversations abound, but are all based in knee-jerk reaction and very generous and misguided uses of political theory and cultural studies.

If anyone involved in these kinds of discussions needs a cautionary tale they only need look back upon the very embarrassing “debates” around poor little Madonna from the eighties and early nineties—we all thought those conversations to be terribly pertinent and relevant at the time, but look at her now! The bitch’s off speaking with a Scottish accent doing God knows what.

I shudder to think at how silly all this will seem once the dust settles, the wind blows in a different direction and we have all accepted the utter hollow and annoying essence of our dear Little Lady Gaga.

May 26, 2010

My partner Juney Bug’s been regaling our readers with the song of the loathsome, fearsome hag. The hag — and don’t get this wrong, ya’ll — is no one to pity. She is not a Christian figure, exactly. No pity and no mercy for the white gal at the end of the bar, please! She don’t need it. She – unlike the rest of us – is Right With God. She, with her tricks and manners, her suitors, a gin and a tonic to lean over, and the end of the night coming on too strong. Like all the Lonely Girls and Barroom Girls, she doesn’t want the night to end. Help our hag keep those colored lights flashing; come closer, and sit down beside her. Tell her a story – if you can get a word in edgewise. And if you’ve got that sad-eyed air about you, fella, hardly a nickel in your pocket, maybe those shoulders carried the weight better in younger days, well then, you just might be the hag’s long lost brother: the beautiful loser. What the hag is to country and down home twang, the beautiful loser is to rock n roll and the Jersey shore. While the hag never left town and her bitterness is deeply grounded, like her moneymaker, into that barstool, the loser couldn’t sit still. You could say he was born to run, to ride his cliché 90 miles an hour down a dead end street. Consequently he is always on the road, lost, and always coming home.

Johnny was a schoolboy when he heard his first Beatles song,

‘Love me do,’ I think it was. From there it didn’t take him long.

Got himself a guitar, used to play every night,

Now he’s in a rock ‘n’ roll outfit,

And everything’s all right, don’t you know?

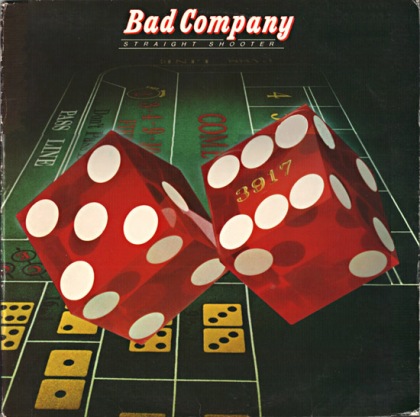

“Love Me Do I think it was” – It’s a quote, of course, and thus the most genuine syllables of a song of love and theft. A long hall of mirrors and the corridors of forgettings and violent crossings out of memory wind the lyric. The stagey way that memory is produced – I think it was — and its middle class, polite locution gives away where these shooting star poseurs come from – mama’s house, or in the case of Bad Company, England. This is the kind of bad company one finds in the discomfort of the suburbs (or 1970s Flatbush), the place where nothing is supposed to ever happen and the blues come borrowed all the way from the Delta through The Stones and Led Zep on to American top 40 ubiquity.

Love me do I think it was. And maybe it was. Maybe it was for me, too. I used to listen all afternoon, piling the stereo arm high with vinyl LPs, the Beatles and Dylan, The Stones, and Judy Collins, Odetta. Where was my little brother? All I remember of David is my excoriating disgust that when offered as a present any album in the world, the fool chose Tom Jones, Live. He actually wanted to listen to an under-talented ass who swiveled his hips at the screaming female fans who threw their panties on stage. It makes sense then that David would go on to love Bad Company. Like Tom Jones they wore tight pants and glittery outfits to accentuate their heterosexuality. Liking them was the mark of a true boy, a suburban, melancholic boy. A white boy, like my brother David.

Johnny told his mama, hey, ‘Mama, I’m goin’ away.

I’m gonna hit the big time, gonna be a big star someday’, Yeah.

Mama came to the door with a teardrop in her eye.

Johnny said, ‘Don’t cry, mama, smile and wave good-bye’.

It’s no accident that mama comes up in the second verse. She is the fount of the loser’s self-love, the lover he wants to escape and to perform for. Little Rockstars are mama’s boys. In their badness — especially in their rebellions — they prove themselves tied ever more to mama. Everyone wants to save the loser. In this bath of unwanted maternal attention the loser perfects defenselessness as the ultimate defense. His signature concession — You may be right – predicts another bender: Hey mama I’m going away.

Remember the hag? The lady sitting at the end of the bar? Well, she’s gotta move over. There’s another sibling rivaling for the bartender’s attention. The lesbian with the dead brother is a new cliché (and oxymoron). We coulda been him. Maybe wanted to be him. Weren’t allowed to be him. Or refused to be him. But in not getting what we wanted or felt we deserved, we survive all the guys we could not be. Poor, unlucky, survivors.

Johnny made a record, Went straight up to number one,

Suddenly everyone loved to hear him sing the song.

Watching the world go by, surprising it goes so fast.

Johnny looked around him and said, ‘Well, I made the big time at last’.

Among my brother’s things is a notebook with cockroach brown pasteboard covers, the kind that you find in old-fashioned office supply stores. In it the tab forShooting Star is meticulously inscribed. My brother took up playing the guitar in prison the way Malcolm X taught himself to read. In prison you do for yourself what you’d let others do for you in the outside world. The results of the loss of freedom can be impressive. By the time his sentence was complete, David played a pretty good guitar.

One afternoon soon after his release, my brother performed an acoustic version of the strangely affable power rocker. He was crashing at our mother’s apartment in Marine Park, one of NYC’s last havens of white ethnics. He was home; I was visiting from grad school in the midwest. I had been circling jobs for him in the local paper. He shot down every demeaning suggestion, but gracefully, without rancor. “This is a good entry level position,” I offered. “You’re probably right” he’d evade. How can a rock star be a bagel boy? Yet as I was playing the sane older sibling I was fighting my surprise at his studious guitar playing. I admit it: I was jealous. You see, I had always been the rock star in the family. I was the one whose band played CBGBs. But I put down the guitar. Who was I to tell him to get real about working some dumb job? Wasn’t I in grad school studying literature, trying just as hard as he was to escape the fate of the ordinary? We both nursed our rock star dreams. Our narcissisms collided, overlapped.

As it turns out, there has always been a job opening for a Shooting Star:

Johnny died one night, died in his bed,

Bottle of whiskey, sleeping tablets by his head.

Johnny’s life passed him by like a warm summer day,

If you listen to the wind you can still hear him play

Don’t you know that you are a shooting star,

Don’t you know, yeah, don’t you know…..

Every beautiful loser sings “Shooting Star” at his own funeral, years before he actually dies, in the mournful cadence of manly self-possession. He’s long down the road from the boy who once cried out “look ma –.” He knows now that no one can look away; no one can ever save him. And it is his utterly calm refusal to be saved that draws us to the beautiful loser. I mean, would you actually want Him to have come down off that cross, knowing his investment in his own sacrifice? Until that afternoon I don’t think I ever realized how fully jealous I must have been all of my life of my beloved little brother, the beautiful loser.

I think David might have learned more about what he wanted in prison than I managed to in grad school. I know he never became a recidivist. Yet I in my way have never gotten out of my institutionalization. No, I seem to even be fighting my way in deeper. And he’s long gone.

But if you listen to the wind you can still hear him play …..

My thoughts so often come back to Dylan, who also wrote a Shooting Star of his own:

All good people are praying/ it’s the last temptation, the last account

Last time you might hear the sermon on the mount

Last radio is playing

Seen a shooting star tonight slip away

Tomorrow will be another day

Guess it’s too late to say the things to you that you needed to hear me say

Seen a shooting star tonight slip away

Maybe Bad Company’s “Shooting Star” is the last song … playing? If so, I often hear its opening guitar chords so balanced, detached, equanimous: All our deaths are sure to come. Don’t You Know?

Don’t you know, yeah yeah, Don’t you know that you are a shooting star,

Don’t you know, don’t you know. Don’t you know that you are

a shooting star, And all the world will love you just as long,

As long as you are.

Filed under: Amy Ray, butch, butch lesbians, Elena Glasberg, freedom, lesbian music, Meridian, nothing, nowhere, testosterone, Uncategorized | Tags: Amy Ray, Bedknobs, Broomsticks, Bruce Springsteen, chicken wire, Elena Glasberg, Joan Crawford, labor, Lesbians, loss, real men!, resignation, sweet sad failure, Taylor Black, Throats, Wayne Koestenbaum, Witchcraft, Woody Guthrie

The Butch’s Throat: “She’s Got To Be” and \”Stand and Deliver\”

Elena Glasberg

03/10/10

I’ve been way too intense these days, way too dramatic. My tendency to take myself too seriously or romantically — let’s call it my tendency in mid life to “fall in love with the first woman I meet/ Put her in a wheelbarrow, and wheel her down the street”– puts me in the Dylanesque category of wizened boy troubadour. It’s an insouciant masculinity based in lusty misogyny and ultimately timed to keep moving on. Though Dylan did once write “Tangled Up in Blue,” about the best most sustained plaint on companionate marriage ever sung. So good that I recognized it long before I ever married, long before I ever broke. I must have known it just from being born to woman and man. But for the most part, Dylan’s love sick blues are lonesome. He’s always showily singing to some idea of a woman and his anger is getting to sound more and more like stand up. “Hell’s My Wife’s Hometown,” another cut from Together Through Life, makes me laugh every time. Dylan stopped singing about real people and feelings a long time ago, though he still reaches me on the deep level of myth and song.

But any protection I might seek from the damage I do to other women and to myself in my wavering, weary boyishness and my inconsistency and bravado breaks down when I pay attention to Amy Ray. “Stand and Deliver” and “She’s Got to Be” are both relationship songs, and in that they are a dime a dozen. Cheesy, even. I’ve never enjoyed the feeling of being hailed by TV ads (phone ads are especially manipulative) or pop tunes. Of course part of maturing or becoming human for the queer child is becoming open to popular feelings, even feeling normal. And now that queer is a brand name, a new way to be incoherent and individual just like every other tattooed sexual deviant out there, I’m even more resistant to the sound track. But oppositional reading and selective insertion of my desires into even the greatest musical fabrics has limits. When I listen to Amy Ray I recognize my nonsense. I feel read, exposed, and even normal. I hear my own struggling voice.

Baby’s got a lot of tears

Enough to cry a thousand years

Enough to cry a thousand seas

Enough to break a boy like me

I want to stand and deliver

Be the one who makes it better.

“Stand and Deliver” deliberately plays with anthemic production modes and structure, the kind intended to hail large rooms of thronging fans. But what theme exactly does Amy Ray seek to politicize? Butch-femme relations? Can an anthem represent queer relations and not monumentalize or reify the fluidity once offered by (and for) sexual resistance?

Even if the answer to these leading questions were not obvious, I’d still enjoy “Stand and Deliver” for precisely daring to speak for me, a lonely striving butch who never feels good enough. Not good enough for womanhood in general, and certainly not good enough for any woman. You can talk about pride and self-knowing, and you can even be really successful with getting men’s wives to sit on your lap (it’s easy, actually). But there’s a part of every deep-in-the-bone butch that can never believe any (real) woman would have her. That’s the butch’s throat, the wondrous contralto from the uncertain center of an unsung identity. Cue the swelling strings and the Robinhood garb:

All I’ve got’s this little chalice

Born of fear and forged with malice

All I’ve got’s this coat of mail [male?]

But in its time it served me well.

It’s useless now as I wither

Why can’t I just deliver?

Forget Robinhood, it’s almost Wagnerian in its endless, swelling drive to cement the lovers and heal the wounded hero with love-death. Sometimes Ray stands behind her electric guitar and delivers, drives forth her contralto from down in her chest, the covered place. This is not a natural voice. I know. I remember one summer vacation in the Catskills making the decision to break the shyness and order an icecream cone. I pitched my voice low, threw it down that hole, tried to feel it supported by my solar plexus, the fundament of my social projection: chocolate cone, please. From that utterance on, that pitch stuck in my butch throat.

No one ever enjoys hearing themselves played back on tape (it’s way more disturbing than a glimpse of yourself unawares in a mirror). The discomfort probably stems not from judgment but more likely from misrecognition: we do not hear ourselves internally the way the sounds come back through recording technologies. Feedback is not so much a reflection as a harmonic disillusion, a rending of our imagined wholeness. Ray, unlike most other butches, spends much of her time working out the mechanics of her voice, its reproduction and circulation. When not standing and delivering she practices the studio croon, the intimate delivery that became possible with the advent of miked recording on radio. In a youtube video, a relatively dolled-up Amy Ray strums directly into the camera, into the microphone, crooning to an imagined audience one swooning femme at a time. It’s a more anxious performance than the one on Wouldn’t It Be Kinder and I’m not sure it suits.

There’s another youtube video of just such an early version of “Stand and Deliver,” lovingly recorded by a fan. It works. Listening, I find myself holding my breath, sort of the way you do at the ballpark when the underprepared kid gets up to sing the national anthem – a notoriously difficult and unlovely vocal obstacle course – and you wonder if they can hit the highs and lows. The same feeling comes over me in this solo acoustic version. The vocal range and delicacy necessary to belt out the prayer, to cast the spell, to produce the butch voice, even more than to seduce the femme (who’s got her own thing going, and I’ll let it alone), makes me wonder, is she gonna make it to the end of this note, to the end of the song?

In the video and on the recording Ray shifts at the end of the song to falsetto, the quintessential male pop voice. I don’t think I any other female singer has ever used falsetto, and there’s a reason: Amy Ray is the butch’s throat, not Patti Smith’s wonderful but still ventriloquized gender masquerade in “Gloria.” No, Amy Ray don’t sound like a man. Close your eyes; there’s no double take/ double listening. Amy Ray is the butch throat. And in “Stand and Deliver” her butchness is cast in relation to doing right, to making whole another woman. It’s not ventriloquism, but something more contrapuntal. Not univocal; it’s anarchy.

As anarchic as it may be, the butch voice springs from one unifying throat or position:

She’s got to be with me always

To make sense of the skin I’m in

Sometimes it gets dangerous

And lonely to defend

Marking time with every change

It’s hard to love this woman in me

She’s the one that stills the seas

Finds the truth in this anarchy

Dives the depth of every age

Keeps this body and knows the shape

I will love. I will protect this love

It was hard to get

I will love and I will protect this love

And it’s anarchy.

Only Ray can occupy the con-tralto boy-like-me position and bypass soprano, the female high voice, bypass also the African-American infused gospel alto that had belonged to singers like Odetta. Ray’s depth and range is less spectacular than K. D. Lang’s virtuoso croon. It’s less self-assured, less placed, more liable to break down and to shift key and pitch mid song and between songs. Her voice is anarchy, the pitched battle of internalized gender.

“Is this body just a cage?” Well of course it is. And that’s why the voice, emanates from the body and yet speaks outside it. This variation on the old body-mind split I call the Gomer Pyle syndrome, after the suspect southern TV army recruit who gaaw-aawl-ied with a country accent, but who burst out in operatic baritone. The voice, unlike the body, does not betray class status or sexuality but does the opposite, it soars away from Podunk, and away from the Viet Nam war. It offers a better alibi than Don’t Ask Don’t Tell. Jim Nabors through his voice became a whole, national crooner, the hopeless white southern faggot no more. Voice can uncage the body, transform status, fool the ear if not the eye. It is always projecting and projection.

But voice is also placed. Voice teachers speak of placing the voice, meaning techniques for producing “head” voice, “chest” or some other foundation for the sound waves to be produced from forced and controlled air through the “pipes” of the larynx and the containing cavities of the torso and skull. Amy Ray’s butch-ly placed sound may overlap with some critiques of the mezzo sound as hooty or covered or dark. But there’s also a boyish brightness or white gospel clarity to her tone, if not emanating from its placement, then from its intention, its innocence and yearning qualities. If the body is a cage, a place for the production of gender and trouble, it is also a staging for a projection. When Amy Ray switches to falsetto, she performs an aural gender trick beyond even the most complex of Strauss’s late trouser role in Der Rosenkavalierbecause it is not only the context of the reception of the voice that changes, and not only how the voice is produced that creates the aural difference, but the final falsetto is a new move in gender’s voiced and performed history: a woman singing low, quoting a man singing high. And the body does not, cannot change. Nor is it a cage, exactly. It is, Amy, a vessel, a location, a passage for air, a bag of wind, a bottom plexus of flesh and energy: it’s anarchy. It’s politics.

Amy Ray is at times as good as Woody Guthrie or Bruce Springsteen when it comes to getting away with politics in song. I could argue that the line “I spent all day pushing tissue roses into chicken wire” from “Put It Out For Good” is the most riveting, alarming, activating image of meaningless and underpaid factory labor in all of rock n roll. But that would be strange, isolating praise. Rock protest tends towards self-promoting anthems of youth and resistance. Even great anti-consumer culture songs like “take this job and shove it” or “(Can’t get no) Satisfaction” prefer the anger of a duped man who thinks his life should matter to scarifying details of other people’s unredeemable labor.

Amy Ray can write an anthem too, though. But people don’t necessarily understand where she’s coming from. It used to be suburbia – the “tramps like us”? . . . Well, maybe not. That was Springsteen’s word for the unsung. Continuing in the American song protest tradition, Ray sings in “Put It Out For Good” for the tramps not like “us”:

All the punks and the queers and the freaks and the smokers

. . . A new gender nation with a new desire.

But lately I think Ray has exhausted the singular field of identity crisis. Reports are that she thinks about the land. She roosts back on that bloody soil of the Las Americas del Sud. The American South. Georgia’s on her mind and in her body. Through Guthrie and Springsteen’s masculine outrage on behalf of outsiders, deportees, the people of the land caught among the map’s shifting borders and their insane walls and real porosity, Ray sings in the voice of the people. But the people never cohered. That’s why Ray’s people are all trannies. No one’s got a home – and no one’s got a righteous purchase on the land. Ray can agitate for the rights of the indigenous, for the people of place, the placed people, even as she speaks for the “new gendered nation,” the people of suburban anomie and placelessness, in a moving voice of contradiction with the power to transport. Long live the butch’s throat!

She’s Got To Be

Taylor Black

03/10/10

When I was very young I wanted to be a witch. No, not in the sun and moon-worshipping, pentacle-wearing way, but a real witch, the kind you see in movies. In fact, my obsession was specifically with the Wicked Witch from The Wizard of Oz, and until I was around seven or eight years old I not only idolized her mentally and emotionally but also dressed as her more often than not. Cloaked in black, witch’s hat in place and riding around my family’s house on a broomstick, I felt most at home in my own skin.

As the years passed and all the confusing feelings and sensations brought on by puberty began to wax, all the imperiousness and dark glamour that influenced my idea of myself as a young witch transformed into what might be generously called a bourgeoning gender and sexual identity. As I ceased riding around on broom sticks and began to ponder my life as a matured adult being I then began to slowly cultivate a different idea of myself as a person found myself drawn to women that were, like Miss Witch: cold, commanding and horribly imposing.

I then spent the rest of my teenage years basking in the glow of these women and this wicked, feminized vision of myself. Luckily, I then found myself able to manipulate my icy form of majestic detachment as a sort of self-defense mechanism as I hurtled through all the drama one might expect for a depraved young faggot growing up in the oppressively masculine, drab Bible Belt South. More tragically, I suppose, I also felt a certain distance —from other people, from lovers, from myself, from my own body.

Living in the ivory tower of my fantasies, I began to feel all alone. And then soon I was. Everything would be okay, would stay in its rightful place, so long as I didn’t look into a mirror. Sex felt alright if I didn’t have to be touched or feel anything good. Friendships were okay if I did all the talking but none of the sharing. Being a member of my family was fine just as long as no one mentioned or thought about my future as a human being, much less as a gendered one.

Fast-forward to my sad, stony face staring around New York City, my new home. Running just as fast as I could out of North Carolina and pointing my toes, or my broomstick, due north, I landed on its shores at age 18, expecting something of a community and some kind of solid sense of identity to come my way. As evidenced in my last piece on Le Tigre’s ode to transmasculinity, the queer world I found myself in was not one I was able to fold myself so easily into. Drunk on (post-)identity politics and the prescriptive narratives and vocabularies that went along with it, I felt even more failed than before. Knee-deep in sinners presumably like myself and settled into a community of queers and a city full of failures, I still felt my obvious lack of identification and hope for my sorry state of sexual abjection and gender dysphoria to be a burden and a source of that same loneliness I’d become so accustomed to.

The central question, at least to me, posed in my bitchy little entry on “Viz” was about the subject of queer anthems, and specifically whether or not the two terms work together at all. While an anthem is meant to celebrate and praise some sort of body—of work, of land, of a person—queerness, at least in my case, is a description for someone who lacks the sort of necessary cohesion to be sung about in such a praiseworthy manner, or even to be praised at all.

Which brings me, however belatedly, to the song that I intended to focus squarely on this week, but that got waylaid by this little confessional. Not just the title for this mistaken autobiography of mine, but also the title of the second song off of Amy Ray’s most recent solo record Didn’t It Feel Kinder, \”She\’s Got To Be\” is the closest to an anthem or to a trans/queer audiobiography that I might be able to relate to.

Odd as it is, I find a lot of myself in this road-weary, road-worn song Amy Ray has written about her butchness and her own relationship to gender dysphoria. Across generations, bodies and sexualities, I find this very personal, yet complicated and even cagey, “anthem” of hers comforting. For better or worse, the song stands out on the album it appears on, but also in the whole of Amy Ray’s catalogue. Following behind the slow drawl of the organ and the almost funky, soulful push given by the bass and the beat comes Amy Ray singing in a boyish falsetto. Her voice is deceptively sweet, sounding almost like some sort of fucked up version of David Cassidy or Donny Osmond. If you don’t listen carefully to the lyrics in the first verse it would be easy to think of the song as a love song for another woman.

She’s got to be with me always

To make sense of the skin I’m in

Sometimes it gets dangerous

And lonely to defend

Marking time with every change

It’s hard to love this woman in me

The first time I listened to the song was at a concert, standing just a few feet from Amy Ray and her band as she closed her eyes and started in on this devastatingly personal and personalizing ballad to her self. Mind you, I’d heard the song a whole lot of times in the weeks leading up to the show on record, but I hadn’t listened to what it was saying. More than that, though, I don’t think it would have willfully occurred to me that a song sung about queerness might have anything to say to me, isolated as I have become in my mixed-up, useless image of myself.

Unlike Samson’s epic ode to her fabulous gender presentation, Amy Ray’s song romances the sadness I’ve felt of not having either. “She’s Got To Be” is everything “Viz” song isn’t: resigned, undone, incomplete and, at least to me, absolutely gorgeous. As I’ve said, you can’t sing a song in praise of some-thing about yourself that you didn’t create or do. If you try and sing triumphantly about a game you can’t win, you’ll lose out in the end. You lost before you began. But, what you can do is sing in the name of your failure—not to over-essentialize or lionize it, but to wrap yourself in it and feel at home. You can stop fighting against yourself if you stop pretending you might be able to win.

She’s the one that stills the seas

Finds the truth in this anarchy

Dives the depth of every age

Keeps this body and knows the shape

The chorus sounds anthemic, but is really more of a spell that Amy Ray casts in her singing of it. Instead of celebrating, it’s creating. It’s resolving. You’ve got to be to be free.

I will love I will protect this love

It was hard to get

I will love and I will protect this love

And it’s anarchy

Standing at the show, drunk on gin and staggered by the weight of what I was suddenly hearing, I began to cry quietly—something, as you might imagine, that doesn’t come naturally or easily to me. The revelation in the song is in Amy Ray’s willingness to give in to herself, to stop fighting and start becoming. Central to my own melancholy regarding any queer or trans narrative I might be able to apply to myself is a recognition that my fantasies and desires—of my self, my body and my sexual expression—can’t translate into anything. This song, like me, is resigned to its failure and in love with its chaos.

The thing that made me cry is the impossibility—of gender, cohesion, language, existence—Amy Ray realizes and demonstrates in her performance of the song. I cried not because I was sad for her, though, but because I knew what she was expressing, felt what she was admitting to have failed at. From my early years on a broomstick to my isolated attempts at finding a home for myself and a useful meaning for my desires, I stood rejoicing in this sweet little song of hers about giving up and staying put. In order to love yourself and become you’ve got to learn to leave well enough alone. Instead of breaking you down, failure can be full of capacity, a way of being and becoming in and of itself.

As I have come to believe in my twilight: when there’s nowhere to go it can feel a lot less lonely and horrifying to stay put, to remain right where you seem to belong. “She’s Got To Be” isn’t a queer anthem, but it’s an anthem to queer-ness; to self-love, instead of misguided self-praise. In place of the noise of rebellion and the silent echoes of loneliness came this song of self-love and affirmation to save me. In every subsequent listen, I remain to be wooed by its sweet sounds of failure, caught up in the romantic melody of resignation.

Filed under: Amy Ray, booze, butch, butch lesbians, Elena Glasberg, freedom, lesbian music, nothing, nowhere, testosterone

Elena Glasberg

02/05/10

Sober Girl

–Amy Ray

I’m a sober girl

not for any good reason

I found myself on this road I’m on

It felt a lot like treason

To my last girlfriends

Who could never understand

When it comes to love I wanted ….. purity

I felt alone in this world in the city so I got out of there

I found myself at the end of a long dirt road

It felt a lot like nowhere

To my last girlfriends……..

When I was young in every camptown song I sung

I was aching just to be …… with someone

Who could lay me down, where rivers run

who was able, who was free…….

Free of this man made world

And all the bargains we made with fear

They slowly whittle us down to nothing

It felt a lot like despair

But I found someone who was still standin when it was done

And with the purest heart she said these words to me:

When I was young…..

Purity. That word that just doesn’t fit in this song and I could never hear it, had to have Taylor translate it for me, several times, in fact. The lyric, its rhythm, just doesn’t make any sense in the context of the song – it always ends the line so awkwardly, against the driving beat. The word is musically unintelligible. It seems to exist on another register of meaning altogether. Who but a lesbian would end a rock lyric on love with the non-rhyme “purity”? But then Taylor’s got to translate so many of Amy Ray’s lyrics for me – I’m trying to get into their heaven, but I seem to live in a far distant psychic world. I’m a Yankee, for one. And a terrible lesbian.

I’m never sure to what extent I care about those sobriety narratives. Or lesbian music culture, which everyone knows exists, if only in some idealized, non-commercial form. Personally, I never listened to lesbian music – no Melissa Etheridge pressing her nose to the heterosexual window, threatening to seduce those straight girls. No Indigo Girls! Only Amy Ray solo for me. These days Amy Ray makes true, complicated butch music. Love her contralto, and her mixedness. I’m interested in the way “Sober Girl” mixes hard rock n roll and the “camptown” songs Amy Ray was subject to in her southern religious upbringing. Funny how the music that accompanies even the most oppressive dogmas probably saved more people than the teachings themselves. Even in my heathenish way, I often feel saved by religious music. I might even say that all music is based in religious practice – in parables and incantations (spells). It can lead to ecstasy — like the twinned guitar solos taking off at the song’s fade out.

“Sober Girl” is the moral-religious soundtrack of contemporary lesbianism. What does it mean to be sober? As a goal it lacks “reason.” And leads to isolation: “treason.” Sobriety requires social revolt and risk. The singer moves from alienated religious childhood, to the bar girls of her young adulthood, finally to achieve self-possession. The song collides on its divergent origins, the church organ entering the ripping guitars and stuttering, free drumming at the “bridge.” Here, the lyrics about wanting to find “someone who would be still standing when it was done” fold into themselves, rondo-like, and it turns out that that “someone” was you all along. The alienated church girl turned into an equally alienated righteous lesbian. Those last girlfriends, “who could never understand” are only the latest exemplars of the ‘man-made world” she needed to flee. I guess you could say, Amy’s (and my) “life was saved by rock n roll” without choking on the irony that a man wrote those lyrics.

The song describes the way I feel about lesbian righteousness and the sub culture’s sad tendency toward censoriousness (that would include a lack of appreciation for lou reed, the rock n roll animal). You know, the identity wars, butch-femme drama, enforced folksiness and general culture of political earnestness that continues in different dress today. Sober is such a loaded term. I’ve always been the sober one at the party. But that’s not the same as being righteous or the one “standing when it was all done.” No, all those drunks can weigh you down. Once (an obviously very castigating) girlfriend even suggested I was a “dry drunk,” a person who, without actually having the fun of boozing manages to display all the pathologies of unsobriety. Well, talk about high and mighty! Sometimes escaping back out that long dirt road seems less like victory than, well, treason. And does treason sort of rhyme with the last word, “free’? Freedom can be more isolating than alienation – at least alienation’s an identity. Freedom can just feel like lost.

For a sober butch in a lesbian culture drunk on righteousness… being the sober butch has always felt a lot nowhere. And now there’s a new substance – testosterone. Everyone’s drunk on masculinity in a bottle, whether they’re taking it themselves or just rubbernecking. For a middle aged butch this is one more scene that “feels a lot like nowhere”…..