Filed under: Amy Ray, deleuze, Dirt, Divine, Dust, exploration, exploration as joke, freedom, Funeral Songs, gay rights, God, hangover, Haunting, Jesus Christ, Jimmie Rogers, Laramie, lesbian music, Meat, Meridian, nihilsm, nothing, nowhere, Spooks, suicide, Terroir, testosterone, violence, Wyoming

She’s Got To Be

Taylor Black

July 2011

When I was very young I wanted to be a witch. No, not in the sun and moon-worshipping, pentacle-wearing way, but a real witch, the kind you see in movies. In fact, my obsession was specifically with the Wicked Witch from The Wizard of Oz, and until I was around seven or eight years old I not only idolized her mentally and emotionally but also dressed as her more often than not. Cloaked in black, witch’s hat in place and riding around my family’s house on a broomstick, I felt most at home in my own skin.

As the years passed and all the confusing feelings and sensations brought on by puberty began to wax, all the imperiousness and dark glamour that influenced my idea of myself as a young witch transformed into what might be generously called a bourgeoning gender and sexual identity. As I ceased riding around on broom sticks and began to ponder my life as a matured adult being I then began to slowly cultivate a different idea of myself as a person found myself drawn to women that were, like Miss Witch: cold, commanding and horribly imposing.

I then spent the rest of my teenage years basking in the glow of these women and this wicked, feminized vision of myself. Luckily, I then found myself able to manipulate my icy form of majestic detachment as a sort of self-defense mechanism as I hurtled through all the drama one might expect for a depraved young faggot growing up in the oppressively masculine, drab Bible Belt South. More tragically, I suppose, I also felt a certain distance —from other people, from lovers, from myself, from my own body.

Living in the ivory tower of my fantasies, I began to feel all alone. And then soon I was. Everything would be okay, would stay in its rightful place, so long as I didn’t look into a mirror. Sex felt alright if I didn’t have to be touched or feel anything good. Friendships were okay if I did all the talking but none of the sharing. Being a member of my family was fine just as long as no one mentioned or thought about my future as a human being, much less as a gendered one.

Fast-forward to my sad, stony face staring around New York City, my new home. Running just as fast as I could out of North Carolina and pointing my toes, or my broomstick, due north, I landed on its shores at age 18, expecting something of a community and some kind of solid sense of identity to come my way. The queer world I found myself in was not one I was able to fold myself so easily into. Drunk on (post-)identity politics and the prescriptive narratives and vocabularies that went along with it, I felt even more failed than before. Knee-deep in sinners presumably like myself and settled into a community of queers and a city full of failures, I still felt my obvious lack of identification and hope for my sorry state of sexual abjection and gender dysphoria to be a burden and a source of that same loneliness I’d become so accustomed to.

Which brings me, however belatedly, to the song that I intended to focus squarely on this week, but that got waylaid by this little confessional. Not just the title for this mistaken autobiography of mine, but also the title of the second song off of Amy Ray’s most recent solo record Didn’t It Feel Kinder, \”She\’s Got To Be\” is the closest to an anthem or to a trans/queer audiobiography that I might be able to relate to.

Odd as it is, I find a lot of myself in this road-weary, road-worn song Amy Ray has written about her butchness and her own relationship to gender dysphoria. Across generations, bodies and sexualities, I find this very personal, yet complicated and even cagey, “anthem” of hers comforting. For better or worse, the song stands out on the album it appears on, but also in the whole of Amy Ray’s catalogue. Following behind the

the bass and the beat comes Amy Ray singing in a boyish falsetto. Her voice is deceptively sweet, sounding almost like some sort of fucked up version of David Cassidy or Donny Osmond. If you don’t listen carefully to the lyrics in the first verse it would be easy to think of the song as a love song for another woman.

She’s got to be with me always

To make sense of the skin I’m in

Sometimes it gets dangerous

And lonely to defend

Marking time with every change

It’s hard to love this woman in me

The first time I listened to the song was at a concert, standing just a few feet from Amy Ray and her band as she closed her eyes and started in on this devastatingly personal and personalizing ballad to her self. Mind you, I’d heard the song a whole lot of times in the weeks leading up to the show on record, but I hadn’t listened to what it was saying. More than that, though, I don’t think it would have willfully occurred to me that a song sung about queerness might have anything to say to me, isolated as I have become in my mixed-up, useless image of myself.

Amy Ray’s song romances the sadness I’ve always had but never clearly felt or understood. “She’s Got To Be” is everything I need it to be: an anthem about losing gracefully. It is resigned, undone, incomplete and, at least to me, absolutely gorgeous. As I’ve said, you can’t sing a song in praise of some-thing about yourself that you didn’t create or do. If you try and sing triumphantly about a game you can’t win, you’ll lose out in the end. You lost before you began. But, what you can do is sing in the name of your failure—not to over-essentialize or lionize it, but to wrap yourself in it and feel at home. You can stop fighting against yourself if you stop pretending you might be able to win.

She’s the one that stills the seas

Finds the truth in this anarchy

Dives the depth of every age

Keeps this body and knows the shape

The chorus sounds anthemic, but is really more of a spell that Amy Ray casts in her singing of it. Instead of celebrating, it’s creating. It’s resolving. You’ve got to be to be free.

I will love I will protect this love

It was hard to get

I will love and I will protect this love

And it’s anarchy

Standing at the show, drunk on gin and staggered by the weight of what I was suddenly hearing, I began to cry quietly—something, as you might imagine, that doesn’t come naturally or easily to me. The revelation in the song is in Amy Ray’s willingness to give in to herself, to stop fighting and start becoming. Central to my own melancholy regarding any queer or trans narrative I might be able to apply to myself is a recognition that my fantasies and desires—of my self, my body and my sexual expression—can’t translate into anything. This song, like me, is resigned to its failure and in love with its chaos.

The thing that made me cry is the impossibility—of gender, cohesion, language, existence—Amy Ray realizes and demonstrates in her performance of the song. I cried not because I was sad for her, though, but because I knew what she was expressing, felt what she was admitting to have failed at. From my early years on a broomstick to my isolated attempts at finding a home for myself and a useful meaning for my desires, I stood rejoicing in this sweet little song of hers about giving up and staying put. In order to love yourself and become you’ve got to learn to leave well enough alone. Instead of breaking you down, failure can be full of capacity, a way of being and becoming in and of itself.

As I have come to believe in my twilight: when there’s nowhere to go it can feel a lot less lonely and horrifying to stay put, to remain right where you seem to belong. “She’s Got To Be” isn’t a queer anthem, but it’s an anthem to queer-ness; to self-love, instead of misguided self-praise. In place of the noise of rebellion and the silent echoes of loneliness came this song of self-love and affirmation to save me. In every subsequent listen, I remain to be wooed by its sweet sounds of failure, caught up in the romantic melody of resignation.

May 26, 2010

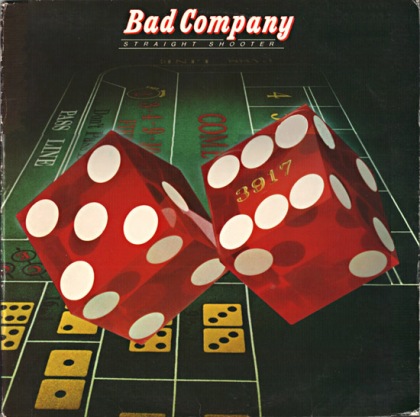

My partner Juney Bug’s been regaling our readers with the song of the loathsome, fearsome hag. The hag — and don’t get this wrong, ya’ll — is no one to pity. She is not a Christian figure, exactly. No pity and no mercy for the white gal at the end of the bar, please! She don’t need it. She – unlike the rest of us – is Right With God. She, with her tricks and manners, her suitors, a gin and a tonic to lean over, and the end of the night coming on too strong. Like all the Lonely Girls and Barroom Girls, she doesn’t want the night to end. Help our hag keep those colored lights flashing; come closer, and sit down beside her. Tell her a story – if you can get a word in edgewise. And if you’ve got that sad-eyed air about you, fella, hardly a nickel in your pocket, maybe those shoulders carried the weight better in younger days, well then, you just might be the hag’s long lost brother: the beautiful loser. What the hag is to country and down home twang, the beautiful loser is to rock n roll and the Jersey shore. While the hag never left town and her bitterness is deeply grounded, like her moneymaker, into that barstool, the loser couldn’t sit still. You could say he was born to run, to ride his cliché 90 miles an hour down a dead end street. Consequently he is always on the road, lost, and always coming home.

Johnny was a schoolboy when he heard his first Beatles song,

‘Love me do,’ I think it was. From there it didn’t take him long.

Got himself a guitar, used to play every night,

Now he’s in a rock ‘n’ roll outfit,

And everything’s all right, don’t you know?

“Love Me Do I think it was” – It’s a quote, of course, and thus the most genuine syllables of a song of love and theft. A long hall of mirrors and the corridors of forgettings and violent crossings out of memory wind the lyric. The stagey way that memory is produced – I think it was — and its middle class, polite locution gives away where these shooting star poseurs come from – mama’s house, or in the case of Bad Company, England. This is the kind of bad company one finds in the discomfort of the suburbs (or 1970s Flatbush), the place where nothing is supposed to ever happen and the blues come borrowed all the way from the Delta through The Stones and Led Zep on to American top 40 ubiquity.

Love me do I think it was. And maybe it was. Maybe it was for me, too. I used to listen all afternoon, piling the stereo arm high with vinyl LPs, the Beatles and Dylan, The Stones, and Judy Collins, Odetta. Where was my little brother? All I remember of David is my excoriating disgust that when offered as a present any album in the world, the fool chose Tom Jones, Live. He actually wanted to listen to an under-talented ass who swiveled his hips at the screaming female fans who threw their panties on stage. It makes sense then that David would go on to love Bad Company. Like Tom Jones they wore tight pants and glittery outfits to accentuate their heterosexuality. Liking them was the mark of a true boy, a suburban, melancholic boy. A white boy, like my brother David.

Johnny told his mama, hey, ‘Mama, I’m goin’ away.

I’m gonna hit the big time, gonna be a big star someday’, Yeah.

Mama came to the door with a teardrop in her eye.

Johnny said, ‘Don’t cry, mama, smile and wave good-bye’.

It’s no accident that mama comes up in the second verse. She is the fount of the loser’s self-love, the lover he wants to escape and to perform for. Little Rockstars are mama’s boys. In their badness — especially in their rebellions — they prove themselves tied ever more to mama. Everyone wants to save the loser. In this bath of unwanted maternal attention the loser perfects defenselessness as the ultimate defense. His signature concession — You may be right – predicts another bender: Hey mama I’m going away.

Remember the hag? The lady sitting at the end of the bar? Well, she’s gotta move over. There’s another sibling rivaling for the bartender’s attention. The lesbian with the dead brother is a new cliché (and oxymoron). We coulda been him. Maybe wanted to be him. Weren’t allowed to be him. Or refused to be him. But in not getting what we wanted or felt we deserved, we survive all the guys we could not be. Poor, unlucky, survivors.

Johnny made a record, Went straight up to number one,

Suddenly everyone loved to hear him sing the song.

Watching the world go by, surprising it goes so fast.

Johnny looked around him and said, ‘Well, I made the big time at last’.

Among my brother’s things is a notebook with cockroach brown pasteboard covers, the kind that you find in old-fashioned office supply stores. In it the tab forShooting Star is meticulously inscribed. My brother took up playing the guitar in prison the way Malcolm X taught himself to read. In prison you do for yourself what you’d let others do for you in the outside world. The results of the loss of freedom can be impressive. By the time his sentence was complete, David played a pretty good guitar.

One afternoon soon after his release, my brother performed an acoustic version of the strangely affable power rocker. He was crashing at our mother’s apartment in Marine Park, one of NYC’s last havens of white ethnics. He was home; I was visiting from grad school in the midwest. I had been circling jobs for him in the local paper. He shot down every demeaning suggestion, but gracefully, without rancor. “This is a good entry level position,” I offered. “You’re probably right” he’d evade. How can a rock star be a bagel boy? Yet as I was playing the sane older sibling I was fighting my surprise at his studious guitar playing. I admit it: I was jealous. You see, I had always been the rock star in the family. I was the one whose band played CBGBs. But I put down the guitar. Who was I to tell him to get real about working some dumb job? Wasn’t I in grad school studying literature, trying just as hard as he was to escape the fate of the ordinary? We both nursed our rock star dreams. Our narcissisms collided, overlapped.

As it turns out, there has always been a job opening for a Shooting Star:

Johnny died one night, died in his bed,

Bottle of whiskey, sleeping tablets by his head.

Johnny’s life passed him by like a warm summer day,

If you listen to the wind you can still hear him play

Don’t you know that you are a shooting star,

Don’t you know, yeah, don’t you know…..

Every beautiful loser sings “Shooting Star” at his own funeral, years before he actually dies, in the mournful cadence of manly self-possession. He’s long down the road from the boy who once cried out “look ma –.” He knows now that no one can look away; no one can ever save him. And it is his utterly calm refusal to be saved that draws us to the beautiful loser. I mean, would you actually want Him to have come down off that cross, knowing his investment in his own sacrifice? Until that afternoon I don’t think I ever realized how fully jealous I must have been all of my life of my beloved little brother, the beautiful loser.

I think David might have learned more about what he wanted in prison than I managed to in grad school. I know he never became a recidivist. Yet I in my way have never gotten out of my institutionalization. No, I seem to even be fighting my way in deeper. And he’s long gone.

But if you listen to the wind you can still hear him play …..

My thoughts so often come back to Dylan, who also wrote a Shooting Star of his own:

All good people are praying/ it’s the last temptation, the last account

Last time you might hear the sermon on the mount

Last radio is playing

Seen a shooting star tonight slip away

Tomorrow will be another day

Guess it’s too late to say the things to you that you needed to hear me say

Seen a shooting star tonight slip away

Maybe Bad Company’s “Shooting Star” is the last song … playing? If so, I often hear its opening guitar chords so balanced, detached, equanimous: All our deaths are sure to come. Don’t You Know?

Don’t you know, yeah yeah, Don’t you know that you are a shooting star,

Don’t you know, don’t you know. Don’t you know that you are

a shooting star, And all the world will love you just as long,

As long as you are.

Filed under: Funeral Songs, Haunting, Lucinda Williams, nothing, nowhere, Pineola, Red Dirt, Southern Gothic, Spooks, Terroir, Uncategorized

World Without Tears: A Devotional, Part 1

Taylor Black

May 2010

Coda:

I climbed all the way inside

Your tragedy

I got behind

The majesty

Of the different shapes

In every note

The endless tapes

Of every word you wrote

Preface: Misery Loves Company

Just as that tired, worn out old saying says: misery loves company. While the remark is normally intended as a kind of passive-aggressive jab directed at the kind of person who tortures their friends, family and really any poor charitable soul who will listen with a never-ending sympathy of complaints and woe-is-me’s, for me, it’s a way of life. As you plunge your self and your own sympathies into this piece, you will see that my own love of misery’s company is really the motor behind all my thoughts and affections, weepy and strange as they may be.

And another thing, dear reader: whether or not you’ve figured it out by now, the string of ideas, gushes and aphorisms that might otherwise be politely referred to as a “paper” will be largely—and, I hope, wonderfully—self-indulgent. There will be more affection in my writing than analysis, and I will concern myself more with how things feel and sound as I say them than defend them as ground-breaking ideas or concepts—I will be writing about music after all. At the very least, I hope you read things you want to hear and that the sight of me wallowing in my own wickedness is entertaining.

We are entering dangerous territory, or, rather, I should say I am entering into a project that’s about my absolute favorite album done by my absolute favorite artist. Why is this dangerous? Well, as most of my previous “academic” work has been conventionally analytical, I haven’t spent much time or intellectual energy lingering on the things in my life that I love. I will shamefully admit that for a long while, my interpretation of doing scholarly work has been about making arguments about things or situating myself into theoretical discussions that have been raging on in one form or another for-probably-ever. In this state of blissful recalcitrance, I found it easiest to make my arguments and my very defensive(?) claims about things I felt a certain detachment from; the idea of responding to and writing about something I love so religiously as music and a figure I identify with so wholly might lead me into embarrassing, confessional territory.

So, with all of that said, I would simply like to emphasize the fact that with this new turn in my work (let’s call it my musical turn for the time being), I am pushing my thoughts and my academic productions away from its defensive, readerly roots towards somewhere and something more celebratory. The joke I brought up in the first sentence will not be, at the end of all of this, on me; as I ruminate on Lucinda Williams’ World Without Tears I will hold it up as an ode to loneliness and despair, all the while doing my own part to draw out and wallow around in the loooove in “Misery Loves Company.”

In terms of a method, mine will be not be very methodological. For starters, you will detect a stark lack of citation in what lays ahead of you—this is not because (believe it or not) I don’t care what other people have to say about Lucinda or any of the musical genres her music and my depictions of her engage with, but because I want to resist the rather litigious urge in academic scholarship to prove what’s said critically and creatively by citing, engaging and situating compulsorily. My thoughts and indeed the sonic space inside my head where they reside and are generated have not come from a vacuum. In similar ways that songwriters can say that this or that piece is inspired by this or that artist or genre, there is a kind of interplay between this paper and the texts—in this case, Wayne Koestenbaum’s The Queens Throat, José Muñoz’ Cruising Utopia, Jimmy McDonough’s new Tammy Wynette: Tragic Country Queen and Hélène Cixous’ Three Steps on the Ladder of Writing— I have been inhabiting during the writing process. While I engage with these pieces to the extent that their thoughts and modes of writing ring in my mind and my ear while I myself do work, I will not attempt to condense or be totally responsible for them, as I try and work with this model of residual, ghostly intertextuality through my own thoughts and feelings.

Secondly, I will confess that the idea of explicitly explaining, describing or deconstructing Lucinda’s music and the album I am approaching gives me even more angst than attempting to be responsible for the contents of a book. Music, like literature and academic scholarship alike, is a process of creativity and failure, and its products and productions should not be approached in order to determine what is they represent or explain, but instead honored for what they do, as well as for what sensations, feelings, misgivings and thoughts they create in the hearing of them. So, just as these authors and these books will be singing their songs in my head while I write, so too while the contents of World Without Tears play while I move from word to word and page to page. As I move ahead, I will rarely approach a song in any literal way or attempt to take it apart—either lyrically or otherwise. Instead, I will let my thoughts and feelings flow against the backdrop of particular tracks on the album, which I will dutifully and possibly excruciatingly play on repeat while I construct the different spaces of my piece. When I have done so, I will list the song and request that my reader try and listen while they read so that they too can sense the rhythm and the affective space with which this piece comes to be. When I do sense a particularly cogent or uncanny relevance of Lucinda’s lyrics for these songs, I will chop them up and place them—in italics—throughout the piece.

With all of that out of the way, I promise not to defend myself or my feelings anymore throughout this work, which is really more like a religious devotional than any kind of academic prose I can imagine. I’m sure I will contradict myself here and there, and my love of Lucinda and tragedy may confound or even fatigue my reader, but I do hope you will at least appereciate my earnestness and the purity of whatever feelings I express here. But why? And shouldn’t I be ashamed at such a disgusting display? Isn’t all of this self-loathing instead of self-loving? Or am I just being ironic? One very easy way to get out these pointed, if obvious, slew of accusations and doubts about my so-called love for misery and the truly miserable would be to revert to some kind of psychoanalytic explanation about being from the Bible Belt South and having internalized and maybe even romanticized all of the most terrible components of the melodramatic Fire and Brimstone culture I was brought up in; or worse, I could simply lean on my identity as a homosexual man and sight some well-known, meaningless tropes about queerness and tragedy as a way of placating you and letting me and my work off the hook as “camp.”

Her Wonderful Wickedness

(Listen to) Righteously

-

-

-

-

- Think this through

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- I laid it down for you every time

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- Respect me I give you what’s mine

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

- You’re entirely way too fine

-

-

-

In all kinds of rather obvious ways, my decision to undertake this Lucinda record is a mistake. First of all, it’s not her most beloved body of work; 1998’s Car Wheels on a Gravel Road is the one album critics and journalists love to love. With its cinematic, narrative songs that weave their ways in and out of moldy, humid corners of the Delta region of the American South, Car Wheels combines just the right amount of folksy realness with meticulously high-brow literaryness to please the kinds of critics who felt invested in roots music but isolated from the explosion of decidedly middling, middlebrow pop music coming out of Nashville. Here you had something as conceptual and sophomorically intellectual as a Bob Dylan or Neil Young album falling from the heavy, weary lips of a woman who had not only conceived of, but actually lived the very southern stories she sung about, all delivered in her thick, muggy southern drawl. Even more exciting for journalists and critics alike was the gossip surrounding and the drama that weighted down the production of the album; taking over four years, three different incantations, three different producers and countless victims employed along the way, once Car Wheels finally came out, Lucinda had managed to gain a reputation for herself as a bitchy, histrionic perfectionist—and (the mostly male) world of rock criticism and journalism still, to this day, can’t seem to publish anything without using that “perfectionist” word, just like no one had ever said it or thought it before they regurgitated it. Leave it to them.

-

- Arms around my waist

-

- You get a taste of how good this can be

-

- Be the man you ought to tenderly

-

- You’re entirely way too fine

You see, or as you already assume or expect, our Ms. Williams is a bit hard to take. For one, she is a perfectionist, and, leaving all gendered epithets aside, doesn’t hide her emotions very well. While most of her fans and critics are both men, their relationship is totally different, and what they see and hear in Lucinda varies completely. For the detached rock critic, weighed down by their strange mix of irony and corporate professionalism, Lucinda’s story is sort of a joke on her, something to talk about ad nauseam.

When you run your hand

All up and run it back down my leg

Get excited and bite my neck

Get me all worked up like that

You don’t have to prove

-

-

-

- Your manhood to me constantly

-

-

-

-

-

- I know you’re the man can’t you see

-

-

-

-

-

- I love you Righteously

-

-

I

The song “Righteously” that is blaring in my ears while I write this is an anthem to power and glory through abjection. In some ways related to Tammy Wynette’s epic song of total, devastating and, in the end, failed devotion to her man, Lucinda’s song is, in some ways, a promise of hers to the man she’s got in her life. However, it’s also a wicked line of flight away from the sentiments expressed in “Stand By Your Man”; beyond and behind her coy promises of righteous love is the real power of this song, which actually, magically stimulates, entices and interpellates her man’s devotion. For the middle aged white men I see at her shows, however, there is a spark in their eyes and a look of abject devotion on their face that lets me know they get it: they don’t look down on Lucinda, they look up at her, and while the sad and sorrowful definitely falls out of her whenever she opens her mouth to sing, it is her fierce, flirtatious and wicked delivery and composure that transforms her tragedies into an elixir that draws her devotees in and brings them down to their grateful knees.

Arms around my waist

You get a taste of how good this can be

Be the man you ought to tenderly

Stand up for me

Approaching Lucinda, Our Beautiful Loser

(Listen to) Sweet Side

-

-

- So you don’t always show your sweet side…

-

Just this side of strange in comparison with the other men at Lucinda’s concerts, I will admit that the main reason I enjoy myself at her shows, though, is mitigated through my sense as well as my perception of her anxiety that is normally—almost ritually—played out each evening she performs in a certain chronology. When she finally makes her way on stage (always very belatedly, in my notable experience), she brings with her an unsettling sort of presence. Lucinda’s affect and disposition is weighed down by a stony, stoic, silent stage fright for the first third of the set, as she moves her way through a handful of amazingly slow, overwrought, plodding, pitiful old songs (the kinds anyone else would tell you to not perform in concert, much less for the first part of the damn set!) allthewhile averting the gaze of the audience and dissociating her from the stage she is performing on.

-

-

-

- You run yourself ragged tryin’ to be strong

-

-

You feel bad when you done nothin’ wrong

Love got all confused with anger and pride

So much abuse on such a little child

Someone you trusted told you to shut up

Now there’s a pain in your gut that you can’t get rid of

After this, thanks to nerves and/or whatever liquor she’s got in her cup up there on stage (she says she drinks Grand Marnier to coat her throat, so there’s at least that…), our once sheepish heroine warms up a bit, maintaining her anxieties and displeasures about her surroundings. Peppering—or, if you’re not into such tenuous forms of spectatorship, cluttering—her performance with false starts and vulgar outbursts, Lucinda has come out of her shell a bit (the last example that comes to mind is her, very seriously and angrily, stopping mid-song to say “Who do I have to fuck to get a fucking fan up here? It’s fucking hot!” Other times I’ve heard her scold people for talking during her set, asking them if they’d like to “fucking do it” themselves)—finally opening herself up to the crowd, only to turn, venomously and breathtakingly, against them.

You were screamed at and kicked over and over

Now you always feel sick and you can’t keep a lover

-

-

-

- You get defensive at every turn

-

-

-

-

-

- You’re overly sensitive and overly concerned

-

-

Few precious memories no lullabies

Hollowed out centuries of lies

A Lucinda Williams concert then, and finally, comes to an end in a flurry of hard-rocking, loud songs that are as frayed at the edges, but orgasmically so. By the time you’re ready to leave, Lucinda has certainly done what a good showman is supposed to do, which is give you your money’s worth by keeping you on the edge of your seat and the tips of your toes. The angst and constant fear of total disaster that guides both Lucinda and her audience through the evening come full circle by the final bows, as she drags out the blaring, cathartic portion of the evening until everyone is drunk and damn well spent. Bill Buford, in his—confused, rather patronizing—depiction of Lucinda published in The New Yorker not long after the release of Car Wheels summed up one of her shows in this way:

- “. . .it’s still possible to see a live show in which she gets a little carried away-and she always seems to be on the verge of getting a little carried away-and hear almost the entire oeuvre, as was the case about eighteen months ago at New York’s Irving Plaza, when Williams’s [sic] encores went on longer than the act, and the audience emerged, after nearly two and a half hours, thoroughly spent, not only by the duration of the program but also by the unforgiving rawness of the songs.”1

What I cannot grasp here—and indeed what I intend to turn on its head, is this very expected, boring depiction of Lucinda as merely a crazy bitch who happens to have written some amazing songs—that being a fan of hers or even being in the presence of her is a thoroughly harrowing thing for someone to be put through—is the lack of empathy that Mr. Buford carries in his self-confessed appreciation of Lucinda’s music. And, of course, he’s not the only person or journalist to put Lucinda and her concert performances in such a glib light (incidentally, a Time Out New York blurb that hinted at possible trainwrecks and meltdowns at one of her concerts was the cause of a night of drama and bitching from Lucinda, who did not get over or stop mentioning it for the entire evening); perhaps this condescending sketch of Lucinda-the-crazy-person is their backhanded, backwards way of complimenting the strength of her music, which they appreciate and understand through very staid tropes of the beautiful loser: the outsider/tortured artist whose brilliance shines in spite and at the expense of themselves (think: Townes Van Zandt, Janis Joplin, Billie Holliday, Tammy Wynette, and on and on). You see, for these folks, Lucinda and her music alike are only fascinating because she’s a train wreck; all descriptions of her, in turn, quickly become cautionary tales.

-

-

-

- You’re tough as steel and you keep your chin up

-

-

-

-

-

- You don’t ever feel like you’re good enough

-

-

Well, as I’ve said and will say again and again, this tale about our Miss Williams will not be a cautionary, ironic or detached one. In order to love her music, you’ve got to appreciate the angst, romance in the disaster and wallow along with her as she moves through her songs and makes them work. True listening is an act faith on the part of the listener—and when the image of the singer/songwriter is just as present in the song as the notes and the lyrics that guide them through, a determined empathy and, dare I say, a religious affection are both completely necessary.

-

- I’ll stick by you baby through thick and thin

-

-

- No matter what kind of shape you’re in

-

Cause I’ve seen your sweet side…

Filed under: booze, butch lesbians, freedom, Funeral Songs, Lucinda Williams, nothing, nowhere, Southern Gothic, Spooks, testosterone, Uncategorized | Tags: hairdos, Hillary Clinton, lonely girls, pretty hairdos, rhinestones

Taylor Black

03/31/10

lonely girls

Forgive me, for, try as I might, I cannot let the hag thing rest. It’s like a song that won’t ever get out of your head.

With this entry, I would like to think about/clarify my own romantic inclinations towards ruined femininity and all the sweet silent solitude awaiting me and all the other lonely girls of the world who live their lives at the end of the bar—living a whole life like it was the end of the night, dancing alone and pretending like we’ve got somewhere to go.

Even as I write this entry, I feel guilty, in part, because I feel I’m just repeating exactly what I said about myself last week—that I longed for the hag’s life; that I have always imagined myself waiting my life out alone at the end of some bar, always there at closing time cloaked in false hope and averting glares behind false eyelashes.

lonely girls

lonely girls

But, sometimes there’s nothing to do but repeat yourself. More staggering than whatever hesitations I have about blogging and, to put it kindly, doing critical analysis about myself the music I listen to, is the image that’s glaring back at me off the computer screen: the image of a lonely girl nursing a gin and tonic that she wishes she could weep into (for dramatic and literary effect, of course) who doesn’t even know how to cry, who can’t even think of something worth getting that upset about.

heavy blankets

While it might be easy to assume that my attraction to failed femininity might have something to do with being a white, gay male, that stock narrative doesn’t work for me…try as I might. You see, my taste tends less toward what you are imagining in your stock narrative of gay masculinity than it is actually, legitimately and tragically aligned not with icons of tragic femininity—Judy Garland, Marlene Dietrich, Whitney Houston, Hillary Clinton—than it is with the actual nameless ruined and destitute women that are, as I speak, sitting by themselves, waiting for something good to happen and singing all the sweet, sad songs that lonely girls do sing. You see, believe it or not, there’s not much irony in what I’ve been trying to convey lately. Forlorn and busted are not qualities that I appreciate, they’re what I am, what I will become.

So, if you’ll allow me one last siren song to close out this hag’s trilogy I promise to be less personal and less overbearing in entries to come. But, with my apologies and defenses out of the way, I’d like to riff off of this song that wrote me long before I tried to comprehend it, that sings the song not only of my life but also of the whole constellation of down and out ladies who are joined with and adhered to me. Their lives rhyme with mine, and together we make up one great big song that never ever ends.

heavy blankets

heavy blankets cover lonely girls

Like the song that I’m burying these thoughts in, the story my face tells and the song that I’ve got to sing about myself doesn’t really go anywhere, even though it probably ought to. Lucinda’s “Lonely Girls” is the first song on Essence, the album immediately following her hugely successful, career-changing Car Wheels on a Gravel Road—a foundational record in the annals of what’s referred to as alt-country, but also simply a whole collection of brilliant narrative-driven songs.

“Lonely Girls,” as you can see, doesn’t have a story to tell…at least that’s not what it’s content is focused on doing…the song really doesn’t even have much content to it in the first place. Like the lonely, ruined women I have been conjuring up the past few weeks as I have attempted to characterize my own romantic image of myself, this song stands alone. There are no metaphors in the song you see before you either, not really even what we think of as artistic expression.

The things that make and cover over lovely girls are not things at all…not descriptions or literary devices but productions, connections, events, stains and always-echoing echoes. You sing the song long enough that you become it.

Rocking back and forth both melodically and rhythmically and not moving beyond the kinds of lyrical descriptions and musical associations normally destined for the first verse of a song, “Lonely Girls” doesn’t go anywhere. However, because of the way the song moves and repeats itself it becomes more like an echo even before you’re a minute in—and when it’s over it’s hard to know how long you’ve been listening; you ask yourself if, perhaps, the song has accidentally gone on repeat.

So goes the life of a lonely girl: destined to repetition and bound to always be too late. I should know.

sweet sad songs

sweet sad songs

sweet sad songs sung by lonely girls

This last verse, I’ll admit, has sunk into my bucket of regularly used phrases—and, if you’ll notice, my blogging—without my even knowing I was doing it. “What a wonderful way to put things, Lucinda,” is the phrase I must have looked over the first minute I uttered the phrase “sweet, sad songs,” assuming it was something I’d come up with myself. But, to her credit as a songwriter and as an alibi for my “creative” plagiarisms, I’d like point out that this is what function a song should play: it sings the story of your life that knew you before you knew it; it makes you a part of the world it creates—fixing you into its lyrics, its cracks, its seams, itself.

Lonely girls may be coming apart at the seams, busted to the gills, broken down and made fragile by their place in the world, but they’ll always have each other; even if they only know themselves through their own personal, languid, remote locations, they know they’re not the only ones out there waiting for their last-call, partner-dancing all by themselves and picking up the pieces that were fractured before the start.

lonely girls

lonely girls

lonely girls

lonely girls

pretty hairdos

pretty hairdos

pretty hairdos worn by lonely girls

sparkly rhinestones

sparkly rhinesstones

sparkly rhinestones shine on lonely girls

Lonely girls

Lonely girls

Lonely girls

Lonely girls

I oughta know

I oughta know

I oughta know about lonely girls

An hour and a half in and I can’t remember where I began. The song’s been playing on repeat for twice as long as that. Filling my glass with one last gin and tonic before bed, I’m getting used to the idea of leaving this piece unbalanced and unfinished…how in the world am I supposed to close a piece up neatly that didn’t really even ever properly begin?

I oughta know.

Lonely girls

Lonely girls

Lonely girls

Lonely girls

Filed under: Dirt, Dust, Frank Stanford, Funeral Songs, Haunting, Lucinda Williams, Pineola, Southern Gothic, Spooks

Subiaco Cemetery Blues

Taylor Black

02/03/10

Last week, I dealt with Emmylou Harris’ eulogy to a red dirt girl named Lillian and ended with the line: “We don’t sing to die, we sing because we’re not dead.” While I can’t exactly say what I meant by this line, or why—aside from the strain of melodrama that weighs heavily on my personal style—I decided to end my piece with it, I can say it was intended in part as a sort of hopeful way out of this particular eulogy to failure. Can singing ever really fall on deaf—or more pointedly—dead ears? What sorts of spells do funeral songs cast over the living?

Magically, “the rare haunting power” of funeral songs surfaced again during my reading of Phillipe Lacoue-Labarthe’s Typography, causing me to consider the ways in which singing in the name of the dead, or about death, casts a spell over life as it’s being lived. Here, in one of his various readings of Theodor Reik’s autobiography, he asks: “What exactly links music to mourning? What links it to the work or play of mourning—to the Trauerspiel, to tragedy?” So, to continue my ruminations on death and sadness, I would like to ask why, if we sing to live, do we sing so much about death? What are the residual effects of our mournful cries, our wailings, our keenings about the deceased for those that remain?

Lucinda Williams’ song “Pineola” was written in the immediate aftermath of the suicide of southern gothic poet Frank Stanford. One afternoon in June 1978, Stanford got into an argument with his wife regarding some of the affairs he had been engaging in with some of the women—Lucinda herself one of them—in and around Fayetteville, Arkansas. He then proceeded to go up into his bedroom and shoot himself three times in the chest. The first lines of the song themselves do more than set the stage for this messy, confusing death—they emote and embody Lucinda’s feelings of shock and discombobulation upon learning of Stanford’s act. In “Pineola,” silence itself is a sound, a spooky reverberation:

“When Daddy told me what happened//I couldn’t believe what he just said//Sonny shot himself with a 44//And they found him lyin’ on his bed.” The whole song is one long response, a kind of primitive mourning. It sounds something like the way you feel when you get punched in the throat or the stomach, like the moment just before you can cry when you feel like the wind’s been knocked out of you: “I could not speak a single word//No tears streamed down my face//I just sat there on the living room couch//Starin’ off into space.”

So many things about this song, and the way Stanford took his life confound me. For one, while performed in its earliest incantations in a sweeter voice, more recent incantations of “Pineola” are more brash and anthemic: it scares the hell of me. In terms of the content of the story, I’m also staggered: How—not to mention why—in the world could someone fire three gunshots into their own heart? What is it about this song that’s so commanding when the only story it tells is of a singer’s lack-of-response to news of death? The answer, it seems, is that it carries power in the noises it creates, and in the echoes of grief it produces. There’s not much to “Pineola.” It’s a simple song, really, but the ways in which it performs Lucinda’s loss of breath and response are heavy and clamorous.

The melody itself is a disembodied record as of Stanford’s death, but also of Lucinda’s feelings surrounding it. As it is performed again and again, all of these things get brought back to life, as Lucinda conjures up the sound of her grief, in her characteristic affectless nasality. Rhythmically, the song lurches back and forth in an a manic, speedy sort of way. Listening to the song, I am haunted by both the image and the feeling of Lucinda sitting, dumfounded, on her family’s living room couch as she heard the news of her lover’s suicide. The emotional direction of “Pineola” results in a eulogy, sure, but it’s also an aural record, a trace, of Lucinda’s spooky wailings – all that we can ever know of “Sonny.”

From red dirt to red dirt in Emmylou’s piece, “Pin-e-ola” drawls out the place of mourning and drops each rhythmic syllables like ashes all over her lover’s grave. As the story closes inside Subiaco Cemetery, to the funeral proceedings for this man who made himself unfit for heaven, you can feel Lucinda’s emptied-out, hopeless presence standing like a ghost in the midst of Stanford’s grieving family members. His mother who, as Lucinda tells us, “got the preacher to say a few words//So his soul wouldn’t be lost,” mourns only in order to absolve herself of any guilt regarding her child’s most unholy death.

Meanwhile, just as everyone around her mourns in unison, Lucinda begins to evaporate and then disappear. The image I have of her at this moment is ghostly, vacant, abject and frightening—not so much because I can imagine it, but because I can feel and hear it too. You see, this eulogy isn’t sung in the name of the dead, it’s sung by the spirit of the living. It is Lucinda—not Stanford—that haunts me. Every time I hear “Pineola,” my sense of Lucinda’s total numbness becomes more intense. Through my idea of her disembodiment I imagine what it must feel like to be a ghost among the living—sort of what it feels like to have someone touch a part of the body that’s fallen asleep. You feel dead. It’s all so wonderfully nauseating to consider.

In the end, Lucinda sings to sing. She mourns to mourn. The last lines of the song, on the other hand, echo Lucinda’s sadness lyrically—as well as thematically, as a casting off all the noises of her own silent sorrow, of her haunting us with them.

“I think I must’ve picked up a handful of dust//And let it fall over his grave//I think I must’ve picked up a handful of dust//And let it fall over his grave”

Filed under: Alabama, Dirt, Dust, Emmylou Harris, Funeral Songs, Jimmie Rogers, Meridian, Mississippi, Red Dirt, Southern Gothic, Terroir

Red Dirt and Aural Terroir

Elena Glasberg

Two girls singing along to the radio, that American jukebox from before the music industry broke down to alt. country, Emmylou Harris’ niche market. In the time after “race records” but way before itunes, the radio connected a nation in sound and could inspire two girls to sing along – and to imagine a life beyond their “red dirt town.” But just you try singing along with “Red Dirt Girl,” and you’ll find that the electronica beat joined by the guitar and then Harris’ sweet voice is deceptively simple. The lyrics — about a doomed girl named Lillian, who “never got any further across the line than Meridian” — come crowding, relentless and yet achingly slow as grief.

It makes sense that the narrative line of “Red Dirt Girl” is driven, as precisely plotted as a road map. Harris says the lyrics came to her while she was driving – a road sign for Meridian started her thinking of rhymes. Lillian/ Meridian, the sounds mixing deep in the red dirt of the border between Alabama and Mississippi. Fixed as this aural geography may be, it also echoes out across the “great big world” Lillian once dreamed of. Meridian, Mississippi, like Lillian, also once aspired to a greater world. During the town’s glory days before WWII, the Mobile and Ohio rail lines intersected there. Jimmie Rogers, “the singing brakeman” left Amtrak for country music greatness. But since those days, Meridian’s fortunes, like Lillian’s, “keep on falling/ there ain’t no bottom, there aint no end.”

Meridian, as the name itself suggests, is an in-between state; it’s a place to pass over and like Lillian’s story, it is easily passed over. It’s the place in-between the wars, in between dirt and sky, earthly blues and gospel’s “joyful sound.” Even today Meridian has among its foreclosed farmland and dying downtown, a church for every 200 inhabitants. Jimmie Rodgers’s lonesome yodeling and the whistle of a locomotive still ring through the air. The red dirt still stains the land; it is a form of terroir — a fancy French term for the trace of origins. We can taste the red dirt in the “off,” or dissonant, rhymes that Harris thought up that day on the road: Lillian/ meridian. Alabama/ hammer. And, Girl/ world – the song’s central dissonance: how to tell a story about a life that isn’t supposed to matter.

“There won’t be a mention in the news of the world/ about the life and death of a red dirt girl.” But every packed line connects Lillian’s life to the greater world. Her brother’s “fixin’ up a ’49 Indian” hints at the violent appropriation and pathetic failure of southern whites with little money or prospects wanting to “ride to the moon and back again” on an old fantasy of Native freedom – but all he gets is a trip to Viet Nam. When the “telegram come” it’s only to tell of the death that predicts Lillian’s own, on the very red dirt from whence she sprang.

Given her losses and sense of entrapment, is it any wonder that Lillian wants to “swing that hammer down”? Foreign wars and domestic misery – the way that meth labs sprout now in places like Meridian like weeds on abandoned train trestles – resolve when Lillian “laid her hammer down/ without a sound.” Like John Henry, she too gave up her struggle for significance: “Stars still fell on Alabama/ the night she finally laid that hammer down.” That hammer, beating you down and beating you up, like the steady beat under the song, still sounds through Johnny Mercer’s “Stars Fell on Alabama,” a hit in 1934, when Meridian still passed as a vital crossroads. All these times and roads, gentleness and violence intersect in the red dirt, the aural terroir of a lost life that tears at gospel sureties and connects to a relentless, “great big world.”

Red Dirt to Red Dirt: Emmylou’s Ode to Joy and Despair

Taylor Black

Emmylou Harris’ “Red Dirt Girl” from her 2000 album of the same name is a perfect song. Like any good work of folk music, the song tells the story of people who don’t matter living in towns that no one knows about. However, this piece is also country and southern gothic down to its core, as Emmylou ruminates on failure and sings the song of sadness. There’s a beat that begins even before the song itself commences. It’s a hammer: the same one we sung about in “If I Had a Hammer,” the same one that made and broke poor old John Henry. In Emmylou’s song she gives a eulogy for a woman she imagines living down in Meridian, stuck in the middle of nowhere with nowhere to go. She’s a well-meaning woman with well-meant hopes and dreams of getting out of her hometown, who ends up swinging her hammer right back down in the same red dirt ground she came from. That same simple, yet insistent, beat that began the song turns into a story, a death, a part of history for this red dirt girl.

Emmylou’s version of Lillian’s life makes elegant what is so terrible about the myth of success for those of us born to fail. You see, there are two kinds of red dirt girls: there’s the one who gets out of Meridian—Emmylou, in this case—and the one who, like Lillian, in spite of themselves and their efforts, has nowhere else to go. However bleak her future was sure to be, Lillian was able to romance the possibility of success for a certain amount of time in her life, wishing and hoping for a way out of Meridian: “She said there’s not much hope for a red dirt girl//somewhere out there is a great big world//that’s where I’m bound//And the stars might fall on Alabama//But one of these days I’m gonna swing my hammer down//Away from this red dirt town//I’m gonna make a joyful sound.”

Those “joyful sounds” of Lillian’s life are textured over the beat of the hammer, as it hammers away at and through the song and the story. As opposed to the simple, confident beat, the words Emmylou uses as she sings about Lillian are complex, overwrought and almost too much to cram into the melody they create. However, Emmylou manages to fit it all in beautifully, poetically and almost magically. Likewise, Lillian’s attempts at overcoming her position in life—“her joyful sounds”—seems to cast a spell over her condition. While the beat of the hammer begins, drives and ends the song itself, the sound of Lillian’s life, of her failure, of her desires, is represented by the sound of her quiet failure—of her hammer hitting the ground without a sound, but with some kind of resounding beauty.

All of the noisy fantasies that inspired Lillian’s mundane life before her future became known to her, before it became the past, ended up only representing something like an ontological blues, which, as Emmylou tells us, “keep on falling because there ain’t no bottom//there ain’t no end//at least not for Lillian.” For Emmylou’s audience, or at least for me, there’s beautiful irony in Lillian’s attempts at optimism and hopefulness. Even before the song admits it to us, Lillian’s fate seems sealed; as Emmylou puts it, she’s bound to die just as isolated and alien as she was born. There’ll be no news about Lillian in The News of the World, and that’s what makes the song tragic like any country song ought to be, but also important as a work of folk music for eulogizing a life that doesn’t matter.

The tragedy for Lillian, however, is not so much that she doesn’t matter—the song is a living testament to her. The problem is all the joyful noise that she hoped would one day grant her wishes of success outside of her predetermined position right there in the middle of Alabama. What Emmylou does so well in this song is to take these sounds and transform them into something else, something more important and transcendent than quotidian desires. Emmylou’s voice, Lillian’s memory and “Red Dirt Girl” itself each cast their own spells. Emmylou sings about tragedy only in order to inspire. You don’t sing to die, you sing because you’re not dead.

![Lucinda_Williams_World_Without_Tears-[Front]-[www.FreeCovers.net]](https://junebugvshurricane.files.wordpress.com/2010/05/lucinda_williams_world_without_tears-front-www-freecovers-net.jpg?w=420&h=420)